We recently talked by Skype with David Dobbs about the mystery that began with his mother’s dying wish. Dobbs’ years of efforts to solve that mystery eventually became “My Mother’s Lover,” which was published last month byThe Atavist.

Dobbs has written at many lengths in several formats: He’s completed three books on science and environmental topics. He’s contributed similarly-themed pieces to The Atlantic and The New York Times Magazine. He blogs for Wired at Neuron Culture. But for this particular story, he ended up turning to the new world of long-long-form publishing, working with Atavist co-founder Evan Ratliff to realize his 12,000-word account of a World War II affair kept secret for five decades. In these excerpts from our talk, he discusses the long struggle to find the right way to tell his story, what rich media added to his words, and the importance of a unifying question.

Did you ever pitch “My Mother’s Lover” to some of the traditional outlets you’ve written for, or did you know you wanted to do something new with it?

Did you ever pitch “My Mother’s Lover” to some of the traditional outlets you’ve written for, or did you know you wanted to do something new with it?

I didn’t know right away, because when I conceived of the story in February 2002, there were not these alternate outlets – there were only conventional print options. My first thought was to write a book about it. I had just finished “Reef Madness,” my third book, and this story grabbed my attention – this story about my mother and her secret World War II lover.

I ran it past my agent and my editor at Knopf. My editor wasn’t wild for it. My agent said, “You should do this book someday, and if you have to do it now, you should do it now.” But as a career thing, it didn’t quite seem right. So I didn’t pursue it then, but I kept doing the research off and on, partly because most of the people involved were quite old, and I was afraid all the sources would pass away.

Then more recently, I pitched it in different forms to a couple places. I pitched a story to Wired that was mainly about the recovery outfit of the government, which is now called JPAC – they’re the ones that go find the bodies of dead soldiers going all the way back to the Revolutionary War. So it was going to be a story about that, with my mother’s story used to hang some human interest on it. They didn’t quite bite.

I sent a 7,000-word memoir to the New Yorker, and they chewed on it a little bit but ultimately passed. Both of those were in the last three years or so.

Was this your first experience doing something not only non-sciencey but also this personal?

It was the first time I’ve written something really personal at this length. It’s not the first time I’ve written about something other than science, because I really first started writing about science eight years ago, and wrote mainly about environmental things before that. I’d written other kinds of stories, but this was definitely a different sort of thing.

Not to suggest that your other work doesn’t make use of storytelling, but this piece relies very heavily on narrative. You have to recreate your mother’s relationship with her lover as well as her relationship with you. Did you have to develop any techniques or skills you hadn’t used before?

I wouldn’t say skills, but I had to approach writing differently. I always try to put a huge weight on story. I think hard about voice, about distance from the story, and about structure.

In a sense, the problems here were very similar to the problems I faced in writing long articles about science. I think readers will carry a lot of weight in a piece about science if the track in front of them is alluring, if the story is interesting. I think the problems were the same sorts of problems I’d dealt with before: What is the right distance for me to have from the story? What do I leave out?

That’s always the hardest thing to decide in a story. There were tons of things that I left out of this story.

You mentioned in an email that the digital long-form format permits some alternative narrative strategies. What strategies were you thinking of in terms of that?

I wouldn’t say it affected my writing strategies hugely. There were places where I could lean on things. There were some freedoms there – a few things you wouldn’t have to describe as much as you would have to normally, but I didn’t try to take advantage of those in the writing.

The story ended up in two formats. It ended up on the iPad, which is a very rich multimedia experience and can add a tremendous value – and does in this case, I’d like to think. But it’s also in a Kindle single, which is a more conventional format. So I had to write it basically as a story that would have a few photographs along with it, but not a whole ton. And in that sense I had to write it as I would for just about any print publication. The value added by the iPad was extra-textual, if you will.

For our readers who won’t have seen the story on the iPad, can you talk about what that rich media included?

The Atavist has its own software for creating these stories, its own kind of content management system. What it does is that you can open a story on an iPad and just read it clean text all the way through. It’s very easy to read. You swipe sideways to move one chapter to the next. You slide your finger up to read down on the page. But there’s a little button on the screen that lets you turn on the extra elements, like the timeline and bios for characters.

The larger thing is that it allows for as many photos as you want. There’s a passage that describes two kinds of planes – a B-17 and PBY – that the rescue crews used. My mother’s lover was a flight surgeon in World War II, in rescue crews that got airmen who had been shot down out of the Pacific. They would land on the water and pick them up or drop a boat to them. I can describe those planes in the text, but in the iPad version, you can punch some links and see pictures of the planes, or in one case link to a web page that shows pictures ofhow the B-17s can survive extraordinary damage in the air and still keep flying home.

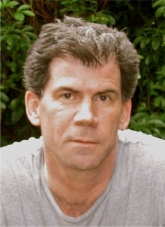

Dobbs’ mother with her lover, Angus

What the Atavist does that I like a lot is put photographs or some visual element between chapters. When you swipe to go from chapter 1 from chapter 2, you have a picture there, or if you want, a video or dynamic illustration. In this case, most of the between-chapter elements are just photographs.

But at one crucial point, about halfway through, I describe these rescue crews of my mother’s lover, whose name was Angus. They found a film, a training film for one of these rescue services – squadrons, they were called. The Atavist folks also found a separate audio file from an oral history, in which one of Angus’ squadron mates, someone who was in his squadron, described the history of the squadron and some of the things that happened in it, including an attack by Japanese soldiers on the squadron’s barracks on Iwo Jima.

So they laid that audio over the training film, and I find it creates a powerful element right smack in the middle of the story. I’ve described in the text the sort of dangers that the crews underwent, and what their experience was like as they followed MacArthur’s forces across the Pacific toward Japan. But on top of that textual description, there’s this little movie they made, with film from one source and audio from another. It’s only about three minutes long, but the mix is very powerful in bringing home to the reader in a visceral way, if you will, what was going on out there in the Pacific.

So here’s a love story about a man who is lost in the war and in a lot of danger. I made a decision not to play up that part of it too much but just get it in there. The film sort of amplifies that in a graceful way and also gives the reader a break right about halfway through a 12,000-word story. These are the kind of things about these enhanced e-books that could really be used in a neat way in all kinds of stuff, including science writing.

They were the ones who found this film and the audio for the rich media, so there was a little bit of a collaboration there?

Very much so. I enjoyed that aspect of this going in. It did feel a little bit more like a collaboration, not to exaggerate it too much. My main job obviously was writing the piece, and I did that pretty much the way I always do it: which is alone in a room, ruminating, trying different things and sharing it with a few friends to get feedback, and then after fixing it, sending it to the editor.

That leaves out a couple things. One is that Evan [Ratliff]is an extremely good long-form writer himself. And knowing that, and knowing that they did one piece at a time, I had the luxury of going over several different options for the story with him. I sent him two previous forms of it: a book pitch that I had written but had not shopped, and the 7,000-word story I had sent to the New Yorker. He knew the material, and we discussed different ways to approach the material. It was very complicated. I thought of six different ways to structure and tell the story.

Once I sent it in, they were extremely active in putting together the multimedia package. I think it’s one of many strengths they bring to this. I had looked, but I had never found the things they had. I found a lot of things but not that stuff.

How would you characterize the structure you ended up using versus the ones you discarded?

The problem with this story was, do I start at the end? Do I start in the middle? Do I start at the very beginning? What’s the main nugget of the story? Is it a love story, in which case you can stop just after the war ends, because all you really need is an epilogue? That’s not the story I told.

Is it mainly a memoir? Yes, it’s mainly a memoir, but … I think every good story has a main strand or a question that’s driving it. So what unifies these different stories that I was thinking about telling? The thing that unified the stories was chasing Angus. People trying to find this one guy, my mother’s lover.

There’s a story about a son trying to reconstruct his mother’s past. There’s a story about my mother wanting to return to Angus. The story begins with my mother surprising her six children by asking to be cremated and have her ashes returned to where her lover is in the Pacific Ocean, because he was shot down toward the end of the war. There’s her, looking for Angus, to return to him. There’s me trying to figure out who he was. There are his children, whom I ran into but didn’t know existed at the start of the story – they’re trying to figure out who he was. So all these things are going on, and ultimately they’re placed in a structure that is fairly conventionally chronological, within a frame.

It opens with a funeral, my brother spreading her ashes in Hawaii. Then there’s a slight backtrack. After that, it goes back to a roughly chronological account, starting with when she was a baby and growing up and then quickly getting to how she met Angus, their time together and then what happened after that, what the reverberations of his disappearance were. And that doesn’t end until the very end of the story, with an action that ends the story, an action taken by me.

There’s a moment in the story where you go to California expecting to find something, and it’s not there. It’s a lovely moment, because it really got me wondering what would happen next. It underlines that not only is historical information hard to come by, sometimes even the facts we think we have are wrong. It gave a wonderful sense of just how complicated this chase was.

That’s why I put that episode in the story. You think you finally have something in your hand that you’ve been looking for a long time, aaaaand… no. It slipped away again. I think all of us who write heavily reported nonfiction, we experience it all the time, but that doesn’t go into the story. What you put in the story is when you finally found it. Or if you didn’t find it, it just doesn’t show up at all.

In this case, it can go in and sort of be an actual event in the story that helps underline the central problem of the whole story that is my mother’s lover. How hard it is to grasp these things, how you’re trying to pin things down and it’s very difficult. This man in particular, Angus, proved elusive to just about everyone.

Is there anything else you want to say about the narrative challenges of writing the story?

I did find it a particular luxury to have a choice of length. Usually, if I get an assignment from The Atlantic or the Times Magazine, they have a range in which they want the thing. They’ll say, “We want five, and you can write it at eight [thousand]. If we love it, we’ll run the longer version.” So there’s a range, but it has fairly distinct borders.

The Atavist said, “Take as much room as you want; just make it the right length for the story.” It really freed me up because I could choose any narrative strategy I wanted, and not have to discard it due to reasons of length.

For more, check out an excerpt of “My Mother’s Lover,” or read a longer talk with Dobbs about his story over at The Open Notebook.