Every spring, the City and Regional Magazine Association names a Writer of the Year, and twice the organization has handed Justin Heckert that honor. Heckert won recently for Atlanta magazine stories about an AIDS survivor, tornado victims, an underground newspaper, struggling standup comics and zombies. The winners aren’t always what the industry likes to call “up-and-coming.” Among this year’s finalists were established magazine writers such as Robert Huber of Philadelphia magazine and Mimi Swartz of Texas Monthly. The other two finalists were Tony Rehagen, of Atlanta and formerly of Indianapolis Monthly, where his selected stories appeared, and Robert Sanchez of 5280 in Denver.

Heckert, who has written for ESPN The Magazine and for Men’s Journal, among others, thinks about narrative in a way that can be helpful to others who’d like to understand how stories work, and to improve their own writing. Instead of highlighting one of his winning CRMA pieces, we’ve asked him to break down all five, from conception to reporting challenges to winning lines.

First, get to know Heckert a bit:

Storyboard: Why did you become a writer?

Heckert: My mother, Pat, was a writer. Is a writer. It starts there. Everything is from her. She was much more prolific when I was younger, writing stories, writing poetry, the best writer I know. And the most imposing figure in that sense. I have a baby book that is about 50 pages, and those pages are filled, top to bottom, with her tiny, impeccable, perfect script, stories about me being born and the first few months of my life. Those words brought me into existence. She has hundreds of poems, some published in literary journals in Missouri long ago. She has been an English lit teacher for 40 years now, teaching the great works to elementary, middle and high school students. The things that influenced her turned out to be the things that influenced me. To this day, I sometimes write a story, and then break parts of the story down into stanzas, like a poem. To get a grasp of the way I want it to sound, or the way it would sound. Also, it is very, very hard, in a way, living in the shadow of someone immensely gifted, a perfectionist. She is often the harshest critic. A few months ago, when I was helping my parents move things into the attic of their home, I discovered a time-capsule-type exercise from when I was in the fifth grade. When asked what I wanted to be, I had written, in capital letters, “A WRITER.”

Heckert: My mother, Pat, was a writer. Is a writer. It starts there. Everything is from her. She was much more prolific when I was younger, writing stories, writing poetry, the best writer I know. And the most imposing figure in that sense. I have a baby book that is about 50 pages, and those pages are filled, top to bottom, with her tiny, impeccable, perfect script, stories about me being born and the first few months of my life. Those words brought me into existence. She has hundreds of poems, some published in literary journals in Missouri long ago. She has been an English lit teacher for 40 years now, teaching the great works to elementary, middle and high school students. The things that influenced her turned out to be the things that influenced me. To this day, I sometimes write a story, and then break parts of the story down into stanzas, like a poem. To get a grasp of the way I want it to sound, or the way it would sound. Also, it is very, very hard, in a way, living in the shadow of someone immensely gifted, a perfectionist. She is often the harshest critic. A few months ago, when I was helping my parents move things into the attic of their home, I discovered a time-capsule-type exercise from when I was in the fifth grade. When asked what I wanted to be, I had written, in capital letters, “A WRITER.”

You’re among a cabal of talented thirtysomething magazine writers who studied together at the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism. You, Wright Thompson, Seth Wickersham − who am I missing? How was that J-school, and fellowship experience, influential?

Tony Rehagen, Diana Raschke, some other people who were in our group, Steve Walentik and Daimon Eklund. Wright and Seth were mentors, absolutely, two of the biggest of my life. I gravitated toward them immediately. Honestly, being there, at this particular moment in time, on the sports desk (I chose sports because it was the only department that sounded interesting to me) − Wright and Seth were the most talented at the paper and in the school. They were a revelation. I had no idea what I wanted from journalism, or that I wanted to do it, until I met them and our sports editor, Greg Mellen. I’d never read a “long-form narrative” story until I met those guys.

I remember something Wright once wrote. It was a daily story about two football players, for anyone else a throwaway story. I was 19 and read this in the paper. This is almost exactly the way it appeared: “Ricardo Rhodes is built like an Ernest Hemingway sentence; short, yet power-packed. Travis Garvin, the other kickoff returner for the Missouri football team, is more like a sentence penned by William Faulkner: flashy, fluid, and known to run-on for days.” They were writing daily stories like this. Second-person stuff, crazy stuff. I can remember most of the ledes both those guys wrote from 1999 to 2001. They were writing columns and longform. I wanted to write like them very badly. I started really trying to find my own voice and immediately tried to write experimental stuff, too. Those years we were there, we would all hang out and talk writing and pick apart each other’s work. And drink, at a place called Widman’s. In my opinion, those guys − well, that’s one of the best classes in the history of the school, and I was there, with them. It was all luck.

You’ve mentioned to me the important role women have played in your writing career. Do explain.

Well, my mother, obviously. That’s the biggest influence and writing presence in my life. She loved Joyce Carol Oates. She taught some Oates, and at a young age I picked up a fiction collection she used to have, that featured the story “The Fine White Mist of Winter” that Oates wrote when she was 19 or so. Then “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?” Mostly her short stories. The writing is so deeply observant and naturally beautiful. Oates — and mom — were both manipulators of language itself. Banal things reminded them of something else, and they would compare objects to other things, colorful and alive. I always want to write this way. That has been one tremendous influence on my writing: the way I see objects, or things, or the way I think about things. I want to describe them how they appear in my head instead of the way they normally appear. This leads to similes, and metaphors, and I know a lot of writers hate that. I know a lot of younger writers (and this kind of depresses me) love to just write in what I would describe as a straightforward style. Also, Rebecca Burns, former editor of Atlanta magazine: She hired me out of school. A huge mentor, in life and in writing.

Why don’t women writers find that same kind of fellowship and support you’ve described, do you think, especially with regard to mentors?

I can only speak from my perspective here, but I was very proactive about this. I sought mentors out. Seth and Wright. Luke Dittrich (now at Esquire, formerly at Atlanta), I picked his brain and pestered him at work, and we became friends. Lee Walburn, the sage of Georgia and editor emeritus of Atlanta, I drove up to his place on my own and sought out his guidance, repeatedly. He did not come knocking on my door. I was always in Rebecca’s office bugging her about something, asking questions, asking for advice. This holds true for everyone. Tom Junod came to speak at Atlanta magazine in 2003, right when I was hired; you damn sure believe I had 50 questions for him, right off the bat. I don’t think I’ve ever had anyone just come to me and offer to be a mentor, or give me advice. It seems like a very proactive endeavor that anyone would have to do in order to get real mentorship.

What’s your end game? What kind of writing life do you most want for yourself and how are you going to get there?

I’d love to be one of the handful of people who have a job at a general-interest national magazine, writing stories. I’d love to have just one editor who I communicate with constantly and who loves my work. Will that happen? I dunno. Seems less likely as time passes.

When young writers tell them they want to be like you, what advice do you offer?

I try and be very positive. I think young writers – in an even younger age group, the next generation – should just read. Everything. That’s one thing about me, and some of the people I know – voracious readers. That’s the only way to learn, and to do this.

Here Heckert breaks down his five winning CRMA Writer of the Year stories:

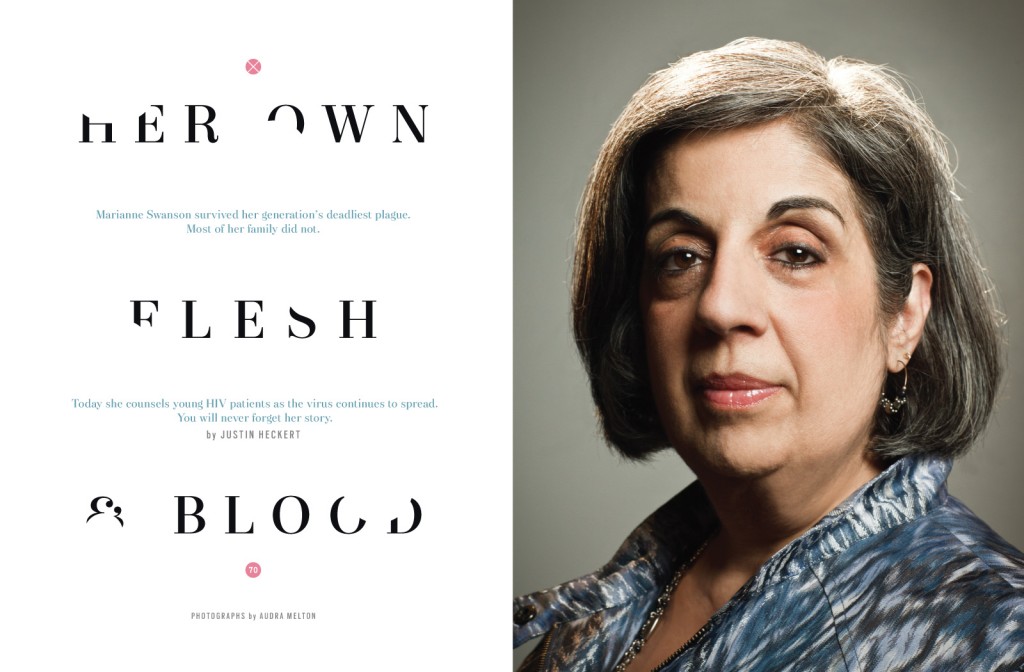

What it’s about: A woman loses her husband and two children to AIDS and, discovering that she is also infected with HIV and on the verge of her own death, must remake her life.

What it’s really about: Survival, acceptance, self-acceptance, love.

A taste:

The Ferris wheel and a funnel cake, just after dusk at the fairgrounds. The big lights blink and the metal creaks to life as he scoots closer to her. After the ride she blows powdered sugar on him and he chases her over the mulch, holding a greasy paper plate, trying to blow some back. He helps her up the steps of the other rides; on the Scrambler he sits to her left, knowing the force will squish her into his arms. He wins her a stuffed horse, which she gives to a kid standing in line. The only thing he wants is to be with her—to be as close to her as he can. He is aware of her story, has heard about all the terrible things that happened to her. She’s sure that no one will want to be with her again.

How the story was born: For several years I’d wanted to write about HIV/AIDS. I find the topic easily one of the most compelling, and most important, stories of the past two generations. I have become obsessed with trying to learn more about its history. Right before I started on the story, before I even had the specific idea, I’d flown through two books − And The Band Played On (a huge book) and My Own Country; I’d watched Common Threads: Stories from the Quilt on Netflix and several other movies, plus a long PBS documentary. I was ingesting all this stuff, and I just knew I had to write a story — now. June of last year was the 30th anniversary of the first CDC report about what was at first called Gay-Related Immune Deficiency, or GRID. That was a time peg but it turned out not to matter at all, really, and the story ran in July. Of course, the story of AIDS has changed; the disease is no longer leaving death in its wake in our country. In the past 15 years, those infected with HIV have not been waiting around to get sick and die, they have been managing relatively normal lives with all the antiretroviral medication available (sadly, not true in third-world countries).

Writing for a city and regional magazine, I find that that’s how most of my ideas come to life: I have an itch to write about a broad subject, or I have a bigger idea, and all I have to do is find a compelling local story and focus. I spent a month and a half floundering, looking for something to stick. I have notebooks of unused material about places and people in the city. There are a lot of people in Atlanta living with HIV, and a lot of compelling angles. I was having dinner with a friend, Tom Lake, and I told him what I was doing. A month of research had gone by. In passing, he mentioned an old family friend, a woman who’d attended the church Tom had grown up in; he gave me her number. I called her. After I talked to Marianne once, I called my editor, Steve Fennessy, immediately.

Biggest reporting challenge: Compiling an accurate timeline of events throughout her life, or two lives, as it were. There were many important names and dates and it was nearly impossible to not become confused about what was happening when. This required hours of re-interviewing her, coming back, asking questions, transcribing, and then picking out and rewriting new questions out of what I’d just transcribed. It was extremely hard work for a 5,500-word story.

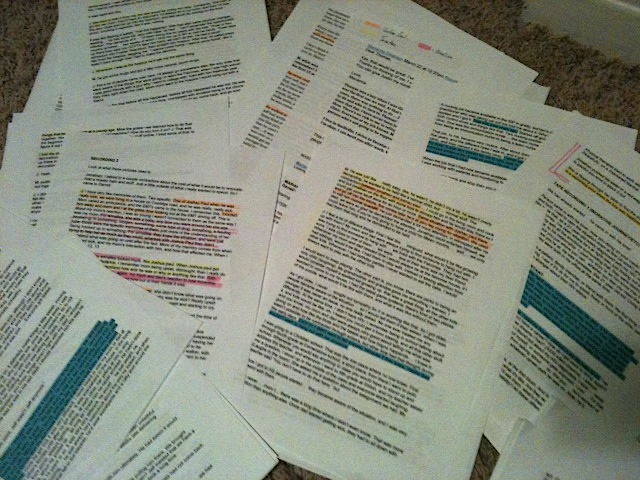

Heckert’s color-coded dialogue system.

Solution: I transcribed about 35,000 words and then used different highlighters for all the names of characters in the story. I would highlight entire sections, a page here and there, or just a sentence, or phrase. Then I cut and pasted, physically, my interviews together so they’d be chronological. All this took up the entire top of our dining room table. This is one of the reasons I ended up using the dates, names, etc., as the structural frame for the story.

Biggest writing challenge: Finding the actual story. What compelled me, initially, was the shock of hearing about all the sadness in her life, the death. Losing two kids and a husband to AIDS? Man, what a story! Well, after I came home and thought about it, after meeting with her several times, and after I tried to write that story of death, it was just too sad. Literally. Too bleak. It wasn’t technically accurate in that way, either, because her current life isn’t sad. It needed some levity, some balance.

Solution: Stepping back, we’re talking about a successful woman here, who has a great job, and a son, and a husband (not that women need husbands). I have to give the credit here to Steve Fennessy, the editor of Atlanta magazine. He asked me to step away from the story several times. Actually, he allowed me to. I wrote about 10,000 words of this before I got an actual beginning. Some of those words made it into the story in other sections, some didn’t. Steve was like: What about now? I mean, what about the present? This has to be a modern story about AIDS. She isn’t dead; she survived. She is a remarkable, living woman. This is a sad story, but is it really a story about death? People don’t really die of AIDS anymore. You know? They don’t. We have to be truthful here. The truth is that she has a very good life right now. In her job, she counsels people; newly infected HIV patients who have no idea about the severity of this thing; she comes home from that job and takes these pills and she has this entirely new life, but reminders of her old life.

So, with Steve’s help — and honestly, I talked to some friends and other people about this story, I was struggling with it so much, but it was Steve with the lantern, leading me out of the woods — I was able to get that dual narrative thing going in the story. I worked so hard on this, I couldn’t look at it after it came out. Now, it may be one of the best things I’ve ever written and I’m super pleased with it, and having met someone like Marianne has enriched my life.

Nice line, editor’s pick: “In Belize, in a cave, they wear hard-hat lights that shine beams into a place as dark and sonorous as anywhere a person could ever imagine.”

Nice line, writer’s pick: “Near the end, she had visited him at Haven House hospice and fed him orange juice and tucked the blankets over his withered legs, had stared at him when his eyes rolled up in his head and sat quietly when he moaned for her to take him home.”

Why he likes it: I like the way it has rhythm. Also, it’s very difficult to boil down a relationship, to distill love and anger and all the little things that go into spending years with someone, and to try and write truthfully about something I’ve yet to experience — spending years with my wife, or having children. This sentence was an ode to them, to what I imagined they must’ve shared, which was gone. She was sitting there beside him as though he were a child, and after all that had happened — you know, he was in this desperate and pathetic state — she was by his side.

***

“Zombies Are So Hot Right Now”

“Zombies Are So Hot Right Now”

What it’s about: The making of a TV show about zombies, and the author’s zombie obsession.

What it’s really about: The monetization of niche geekery? How much we like scaring ourselves either with what we are or what we could become? Or, hey: zombies!

A taste:

The moon has risen like a corpse from a tombstone and hangs gray above Newnan High School. During a break from eating people, zombies light cigarettes and sit on the grass. They lumber across a gymnasium parking lot that has been turned into a FEMA camp, past a television production tent with three screens and producers sitting in monogrammed chairs. They pass two dozen crew members, a long metal jib with a camera attached to its end, and gather near us, the living, in this phantasmagoric heat. The zombies have been moaning on camera, slouching and leering, baring their teeth. Contact lenses imbue a miserable hunger into their eyes. They wear tattered clothing, dried with fake blood and damp with sweat.

How the story was born: I wanted to write about The Walking Dead. Specifically, from the point of view of a zombie extra. I wanted to be in the show, and write from that perspective, the perspective of an actual zombie, what it was like in my own imagination and what it was like actually being a show zombie, working. The story would ultimately be about my fascination and love of zombies, and also … the show, and its popularity.

Biggest reporting challenge: Getting an okay from AMC to be a zombie extra and then having them inexplicably pull the plug late in the game, with no big explanation. I was so angry. And frustrated. Writing the story from the perspective of being a zombie was my vision of grandeur. I got barely any access after being told we’d get a lot. The access I did get? Through a friend of a friend, whose brother worked on set. I mean, I wasn’t supposed to be there. The access amounted to a few hours in and around the set. And an interview with IronE Singleton, one of the characters, at a graveyard. The PR person was sitting next to us on the lip of a tombstone.

Solution: Where do I begin? I had to write a magazine story about the show; I still wanted it to be about my love of zombies. I had to start over with a different idea, a bigger idea, than just, “This is going to be about the show, and my love of zombies.” With little access, I wasn’t sure exactly how to do this. I began searching around. I already knew Atlanta was a great horror town, with a great horror scene. But a little Googling showed it to be zombie central. After about a solid day of reading around online, I typed out this phrase in a Word document: “Atlanta really is the zombie capital of world.” That ended up being kind of the point of the story. Suck it, world! I started it.

And — it blew up. For example: A few weeks after the story came out, I was pleased to see that the New York Times reads Atlanta magazine: They wrote a story off my story, using the phrase I’d freaking coined! I mean, it’s their lede. Of course, I went and bought several copies of the paper. Now, this phrase has become an accepted part of the Atlanta lexicon; It’s on Atlanta’s Wikipedia page. Other cities are pissed about it, apparently.

Biggest writing challenge: This was fun to write. The only challenge was deciding to use first person or not, since I wasn’t a zombie extra. Did we really need it?

Solution: I ended up using the first person, because I felt, yes, we needed it. The genesis of this story was always the fact that I loved zombies. Ask Steve and he’ll probably say it’s because the magazine wanted a story about the show. I used first person only so I could write the second section. The story still had to be personal; it’s a personal story, I think, or at least it comes from a personal place. It’s not just about the show to me.

Nice line, editor’s pick: “The geeks lurched into the city last summer, taking over seven square blocks Downtown.”

Nice line, writer’s pick: “Contact lenses imbue a miserable hunger into their eyes.”

Why he likes it: I spent a decent amount of time trying to describe them, even in one sentence, in a new way. To add something to all the zombie “literature” (hey, there’s a lot!). I think that’s actually how zombies look: not just miserable, not just brain-dead but hungry. There’s something deeper, like they have to eat brains but maybe they don’t want to. Hence, that line.

Storyboard: Breaking format for a minute, we’d argue that the line reads better this way: “Contact lenses imbue their eyes with a miserable hunger.” Let’s fight about it.

Heckert: The first one reads better because it ends with “eyes” and not “hunger.” Also, the “with” slows the sentence down.

Storyboard: “Hunger” is a more evocative end word. It creates feeling. “Eyes” doesn’t. And what’re you talking about, slowing the sentence down? Choice No. 2 has a lovelier rhythm. Loveliness being what you want, of course, in a zombie story. Read it out loud. Do you read your stuff out loud? Are you a hair-pulling edit? Did Steve grow gray, with you in his stable?

Heckert: I read aloud in my head. The way I write is: I write one sentence. Read it. Then write another. Read both of them. Write another. Read the three of them. Write another. And so on, until I have one section. Then I read the entire section before starting the second. Then over and over again. We wouldn’t even be talking about this had I not written that sentence in the first place. Which is the way it sparkled in my head. It’s hard to create something that no one has said about a certain thing before, be it the ocean or zombies. I still like mine.

Storyboard (sighing deeply): Yeah, but you have to be able to let go of the process and the victory. It’s the local-level equivalent of killing your darlings. You did write something unique but it’s no less unique if you then take it one step further by smoothing out the cadence.

Heckert: Here’s something: (In “The Town that Blew Away”), “Vaughn, Georgia” became my “cellar door.” I found the two words to be almost entrancing when placed together. Hence, I wrote them down immediately and knew I would build everything after those two words.

***

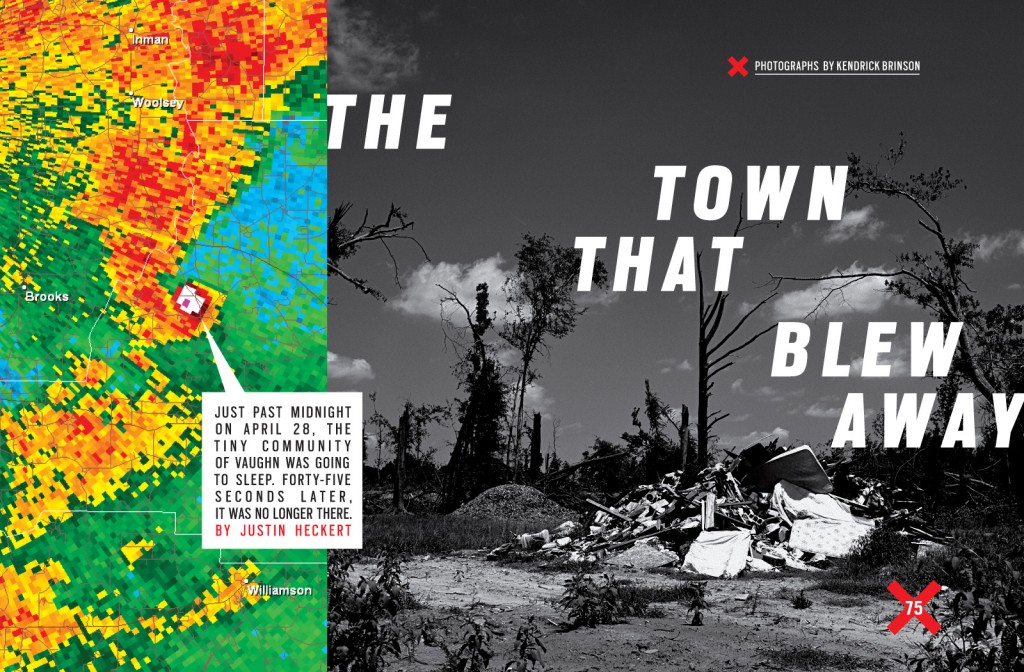

What it’s about: A tornado that destroyed the town of Vaughn, Georgia.

What it’s really about: One of the most important things that defines us: a sense of place, and what is lost when that place disappears.

A taste:

And it was also weird what the tornado did. For instance, it picked up John English’s lone picture of his father and placed it all the way across the road, without a scratch on the glass. It took the tomato plants but left the beans. It took most of the house but only blew over his grill and bent a side of the pool. It took away the play set but left the air-conditioner. It took some big, comfy chairs and two Bradford pear trees right out of the ground, but didn’t take the porch fixture or the butterfly plant in the bowl. Next door to the Englishes, in an old house everyone thought used to be a hotel, a man named Kenneth Youngblood lost his porch, some windows, part of the roof on the back, but that was all.

How the story was born: While working on zombies, I was south of Atlanta, near a town called Senoia. I was riding on a back road, in the woods, with one of The Walking Dead crew. He took a wrong turn, or I would’ve never written this story. After he took the wrong turn, and we drove past the place he was looking for, we came upon a scorched opening in the woods. The forest had been obliterated and there was a small area of immense devastation. In the middle of the waste — concrete, dirt, cinderblock, flattened and broken trees — one person was rebuilding a house. I don’t see tornado destruction very often, so this really … amazed me. Then the woods began again, thick trees, and we continued on. “That was Vaughn,” the crewmember said. “A big tornado came through here. Completely destroyed that town.” I’ve read plenty of tornado stories before, but I’d never written one. Just briefly passing by Vaughn, and seeing it was no longer there — I told myself to come back and find out what happened. And if anyone was staying, and why. And I wanted to know more about the place. So, I went back. I really wanted to explore that idea, about a place being totally wiped off the map. You know, for instance, Joplin was really bad; but not all of it was destroyed. Most of it still remained. Vaughn was completely erased.

Biggest reporting challenge: Getting the residents to talk to me, and feel at ease when I visited every day for two weeks in a row.

Solution: First, I had to find Vaughn and get back there. It’s not even on the map anymore. It’s technically a part of Griffin. Several tornadoes (a near-historic number) hit the state on the same night. But there was, literally, nothing in the news about Vaughn. This is one of those instances where my story was going to be the only story. I felt a sense of responsibility to kind of, I don’t know, write the town back into existence, while also providing its epitaph. I saw a photo on the Georgia Red Cross web site showing a church that had been leveled by one of the tornadoes, and the caption in the photo said something like “Vaughn United Methodist Church.” The picture was the only thing I found on the Internet. I called the Red Cross. A few calls led me to the pastor of that Vaughn church. I asked her to take me into the ruins of the town. She put me in contact with another woman, named Brenda Wolf. She knew everyone in town. I met her at a McDonald’s one morning and she took me to ground zero. We met the pastor there. One of the men — the mayor, John English — was standing outside in the ruins. Brenda introduced me. I spent two days visiting with Mr. and Mrs. English; they introduced me to the sheriff, and so on. I told them I would come back every day until I had talked to everyone — 20 people or so — who had lived there. One of the residents was in jail, and I talked to him. Coming back every day, I think that let them know I was really serious about this. I would come back in the morning and stay all day. Several people were always out smoking cigarettes under a tent. People who were rebuilding their homes, just sitting out there in the wasteland. They began to expect me, and then grew comfortable with my presence.

Biggest writing challenge: I am a firm believer that the beginning is by far the most important part of a story. An ending of a particular story may be a letdown, but that’s nothing compared to not wanting to read the story in the first place because the beginning is boring.

Solution: I spent a lot of time trying to decide how to begin this one and also how to end it. When I came back from my first visit to Vaughn, I typed “Vaughn, Georgia” into my Word document. Those two words were my “cellar door.” They were beautiful together. I typed them, and then at some point I finished, “was a good place to live.” That sounded really nice. And true, of course, according to its former residents. It wasn’t a great place, or the best place in the world; just a good place to spend a life. The rest of the beginning is somewhat about repetition, and rhythm: “It was a place … it was a place … it was a place …” and so on. Those sentences seemed to really snap off my keyboard. I thought those lines sounded great in my own head. I used metaphors in this story, and foreshadowing, two qualities of fiction that are always important in my work, whenever I can use them: The pigeon coop, and the tree next to the trailer, before it fell and saved the family, factor in at the beginning and also big-time at the end. Simple foreshadowing. The pigeons and the metaphor of them are a bit of a different matter. Half the people there looked at the tornado as a sign of God, the fact that they were spared. The others saw it just as a tornado, as a bad stroke of luck, as just something that happened. Half called the pigeons “doves” and vice versa; some saw them as beautiful, as a symbol, and others saw them as just pigeons. You can call it both ways, but that was very beautiful and haunting to me.

Nice line, editor’s pick: “The pine branches had begun to pop and dance.”

Nice line, writer’s pick: “Tired vehicles slouched in the yards, yes.”

Why he likes it: The cars and trucks in Vaughn, how the place used to look in pictures that I saw before the tornado, they were just parked in the grass, some of them broken down and junky. This made me think of old dogs slouching or drooping on porches or in yards, just sitting there as the days passed, as they do in these little Southern towns. So, I liked the way that sounded.

***

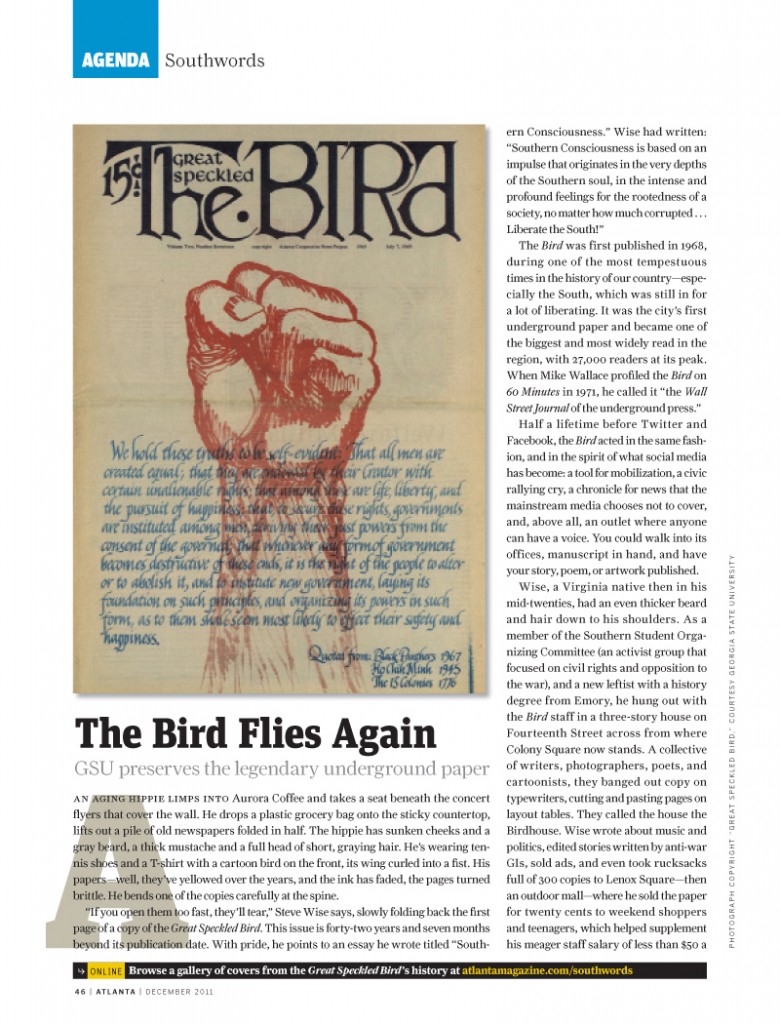

What it’s about: Atlanta’s first underground paper, which Mike Wallace, on 60 Minutes, once called “the Wall Street Journal of the underground press.”

What it’s really about: A moment in time.

A taste:

An aging hippie limps into Aurora Coffee and takes a seat beneath the concert flyers that cover the wall. He drops a plastic grocery bag onto the sticky countertop, lifts out a pile of old newspapers folded in half. The hippie has sunken cheeks and a gray beard, a thick mustache and a full head of short, graying hair. He’s wearing tennis shoes and a T-shirt with a cartoon bird on the front, its wing curled into a fist. His papers—well, they’ve yellowed over the years, and the ink has faded, the pages turned brittle. He bends one of the copies carefully at the spine.

How the story was born: During a break in the Decatur Book Festival last year, after hearing one of the featured authors read for an hour or so, I went into the Decatur Courthouse with my wife and mom to beat the heat. Right inside the door, in one of the exhibit rooms, was a big retrospective on The Bird. The walls were covered with old photos, slogans, articles, covers of the paper, shiny, laminated artwork, a timeline spanning the walls. I felt like an imbecile — I’d lived in Atlanta for eight years and never, ever heard about it. I knew nothing about it. Standing in that exhibit reminded me of being a young boy, hanging out with my mom in the darkroom of the old newspaper at Scott City High School in Missouri, smelling the ink and looking at the photos soaking in their bins. I wasn’t alive in the ’60s or in eight years of the ’70s but I had this huge buzz in my head, right then: If I had been, working for The Bird is something I would’ve wanted to do. I told Steve that I wanted to write about this paper immediately. He indulged my curiosity. I knew this was going to be a short story, but I felt a personal need to write it. It was all about me.

Biggest reporting challenge: Trying to ask smart questions to the self-described hippies in the story. I would describe all of them as intellectuals, and former reporters and writers, obviously. And they were slightly … imposing, I suppose.

Solution: I did a shitload of research about The Bird and about those decades in Atlanta. This was one of the only stories I’ve written in a while where I wrote many questions down before I interviewed each person. I didn’t just go in there and try and start up a conversation and see where it led.

Biggest writing challenge: Trying to figure out how to write the story in 1,700 words, and make it have a life. I really wanted to make it about the feeling the paper conjured inside me when I discovered it there in the courthouse.

Solution: I had only a few days to write it, so I chose a very straightforward approach. I don’t often like to write things this … straightforward. Looking back, I wish I’d taken a riskier approach. I do remember writing the story and being cognizant of the fact that I’d used the word “The” to begin nearly every story I’d written in the calendar year. I don’t know why, but this was something I was now desperate to avoid. So, after much deliberation, I decided to begin this story with “An.” I had this internal monologue: “Only a hack would use the word ‘the’ so many times in a row to begin a story.” I know that sounds dumb. But that’s the way I often think, and not just about first words.

Nice line, editor’s pick: “Now they are an old married couple, both in their sixties, who often pedal around town on their recumbent trikes.”

Nice line, writer’s pick: “He bends one of the copies carefully at the spine.”

Why he likes it: This was one of the only human moments in the story. The guy was really protective of his keepsake copies. They really meant a lot to him. That character — none of the characters really turn out to be three-dimensional, that’s just not the kind of story it is. This is just a small insight into this character with whom I talked for about six hours.

***

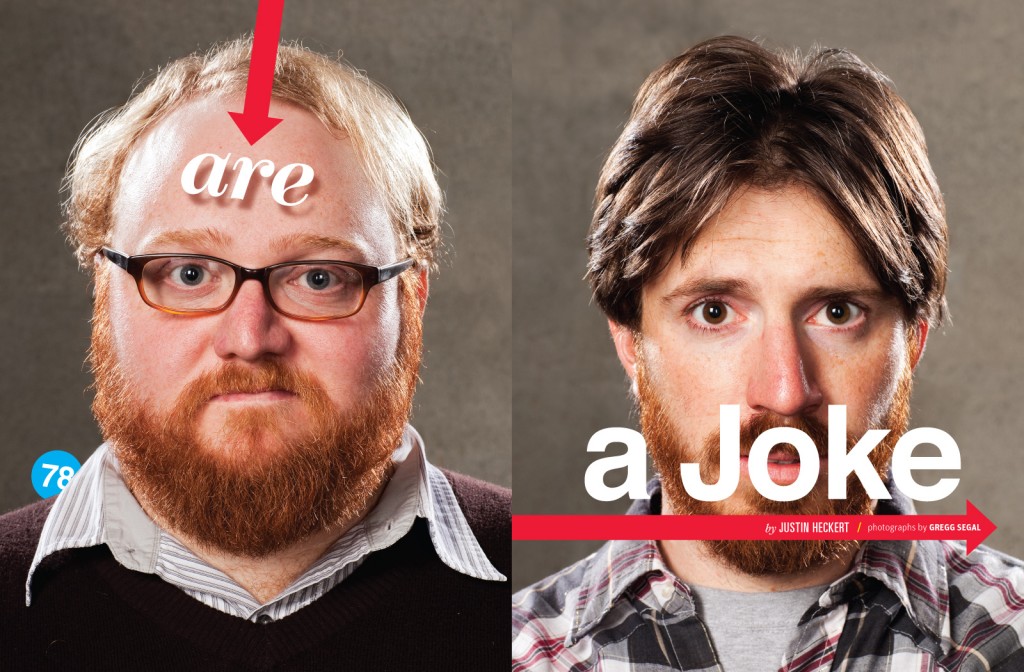

What it’s about: Four hirsute comics known as the Beards of Comedy do a West Coast tour, ready “to be serious about being funny.”

What it’s really about: Resilience, determination, hope.

A taste:

The journey wore on them. The road wore on them, as it curved into the mountainside. For five days, the Beards of Comedy had stared at the gray of the highway, and the cold and the dark had worn on them, too. They’d eaten potato chips and CornNuts, Big Macs and Subway footlongs, candy bars and cookies that left crumbs in their facial hair. They’d whizzed in the stalls of a hundred rest stops, devoured two loaves of white-bread sandwiches made with honey and Walmart peanut butter. They used luggage as pillows, bags of dirty clothes as armrests, discarded their refuse into the seat pouches and door slots and onto the carpeted floor of their rented Tahoe.

How the story was born: My wife, Amanda Heckert (editor of Indianapolis Monthly), and I went to see some stand-up at the Laughing Skull Comedy Club in Midtown Atlanta. Afterward, I said: “I’d like to write about these people.” So I spent a month in Atlanta going to shows nearly every night; big clubs, small clubs, black clubs, white clubs (like everything else in the city — like Ryan Cameron said — there’s a Black Atlanta and a White Atlanta); and I was going to write about the different comedy scenes there, the different people. But there was no natural storyline. I just had dozens of interviews with different comics, talking about themselves. Talk about depressing! Steve Fennessy, my editor on all but one of these stories, was like: “Okay, what are you going to do with this material?” I had no idea. One of my last interviews in this series of interviews with ATL comics was with Dave Stone, the guy with the Elizabethan beard. He mentioned their first big road trip. My ears perked up, and I asked if I could go.

How the story was born: My wife, Amanda Heckert (editor of Indianapolis Monthly), and I went to see some stand-up at the Laughing Skull Comedy Club in Midtown Atlanta. Afterward, I said: “I’d like to write about these people.” So I spent a month in Atlanta going to shows nearly every night; big clubs, small clubs, black clubs, white clubs (like everything else in the city — like Ryan Cameron said — there’s a Black Atlanta and a White Atlanta); and I was going to write about the different comedy scenes there, the different people. But there was no natural storyline. I just had dozens of interviews with different comics, talking about themselves. Talk about depressing! Steve Fennessy, my editor on all but one of these stories, was like: “Okay, what are you going to do with this material?” I had no idea. One of my last interviews in this series of interviews with ATL comics was with Dave Stone, the guy with the Elizabethan beard. He mentioned their first big road trip. My ears perked up, and I asked if I could go.

But the deeper impulse was this: This is the very first thing I’d written after working five years on contract, as a contributing writer on the masthead, at ESPN The Magazine. I mean, this is the first story I wrote in light of turning down quite a bit of money to stay at the magazine in November 2010. They had offered me a three-year deal, which is huge stability in this industry, at a national sports magazine. People at the magazine were always very good to me, and I really liked all my editors. My decision to leave was about the creative process as a whole. I wanted to avoid having five or six people edit each story before it was in print. In my experience, that just doesn’t really work. So, my gut told me it was time to leave. I’d written a story a year earlier, “Lost in the Waves,” and the success of that story, that I could write it and get it published, was an affirmation of the type of work I wanted to do.

So I’m 31, not sure AT ALL I’ve made the right decision, wife at home supporting the hell out of me, financially and emotionally. And I’m on this road trip with the Beards and one morning I wake up in Portales, Ariz., in some shitbag hotel, to Taco Bell wrappers and lettuce and cheese on the bed, to the smell of a chicken pot pie — one of these guys is ironing his only pair of jeans, and, as he says in one of his bits, that’s really what jeans smell like after you iron them every day for a couple weeks, and don’t wash them. They smell like a chicken pot pie. There were empty Coors Light bottles and Little Caesars boxes on the floor. Going in the bathrooms, stepping out and gasping for air, and lighting a match and yelling, “Jesus!” This was just the life on the road. The Beards were all in their early 30s, too. They were technically barely making it, but they had a real hunger for what they were doing. They talked about comedy like I talk to my buddies about writing, wanting to be great at it. They were very serious about it at this point in their lives, and they were good. It was this, or it was nothing. So, honestly? This was a story about me. About failures, hopes, artistic aspirations, wanting to be great at something, not sure about the future. The story coincided with this big decision in my life, and I was frightened, and hopeful, and curious about my own abilities and, using a line I used with one of the Beards, with bigger dreams that I couldn’t ignore.

Biggest reporting challenge: I had as much access as anyone could ever want for a story. The biggest challenge was trying to fit in with them; to not be some weird fifth wheel; to seem like I wasn’t “there.” Try and get them completely comfortable with my presence.

Solution: I grew a beard! Also, I didn’t ask any questions the first few days. I just tried to laugh with them and occasionally, subtly, join the dialogue. At one point, to make them laugh, or to ease the fact that I was there, or something, we met some nice older ladies at the first show they played, at a small university, and I introduced myself as “Mitch.” The Beards knew this wasn’t my name. I said it real loud, because MITCH is a manly name. This cracked them up.

Biggest writing challenge: Finding a beginning. The road and the shows blurred together. Everything blurred together. I came home from the trip. I had dozens of hours of tape (I would often just turn the recorder on in the SUV while they were talking). I had taken hundreds of pictures with my iPhone. I just had a ton of “stuff,” everywhere I turned.

Solution: I put all that stuff in a drawer, and just stopped transcribing. I realized I could just remember everything, pretty much, except for exact lines of dialogue. I sat down and started typing, at a very vivid remembrance, several days into the trip, having seen the scenery, having smelled the smells, having been with the Beards, having been worn down by the nights and the mornings. That was a place in the story that kind of summed things up for me, a place where I could put the reader into the middle of the story and then take them back to the beginning.

Nice line, editor’s pick: “TJ was behind the wheel, just north of the Hoover Dam, and the evening sun looked like a single coin flipped into an empty sky.”

Nice line, writer’s pick: “There were a lot of tourists, a lot of young people, a lot of weirdos, a lot of leather pants and short skirts, football jerseys, an insufferable number of sunglasses, a lot of mumbling and disoriented dudes, a lot of women walking two- and three-by-side, holding oversized, plastic beer bottles, aimless wanderers floating beneath all that flickering neon, begging for something interesting to gobble them up.”

Why he likes it: Well, first, that’s one of those passages that I just wrote really quickly, and liked. One of my favorite parts about writing nonfiction is doing stuff like that, the “exposition.” I mean to say, one of my favorite things is to not “get out of the way.” I had the jones to write something about Vegas that no one has ever written before. “Begging for something interesting to gobble them up…” — that’s just what people are doing.

*Spread designs courtesy of Atlanta magazine

“

“ “

“ “

“ “

“