A couple of years ago, in a Storyboard piece on John McPhee‘s gorgeously built Encounters with the Archdruid, the acclaimed author Adam Hochschild wrote about narrative structure:

A few years ago I was with a young cousin, a college student who told me she was majoring in civil engineering. “I’ve never really understood,” I asked her. “What’s the difference between an architect and an engineer?”

“Ah,” she said. “An architect is the person who plans what the skyscraper is going to look like from the outside. An engineer is the person who makes sure it doesn’t fall down.”

I’ve always felt that when we think about writing, we pay too much attention, in these terms, to the architecture, and not enough to the engineering. We focus on the outside of the skyscraper – the sparkle of someone’s prose, images, metaphors, bits of description – and not enough on the innards: the structure, the plot (a word that applies to nonfiction as much as to fiction), the careful doling out or withholding of information to create suspense, all of which, in the long run, ultimately determines whether or not we keep on reading. A piece of writing can sparkle aplenty from one paragraph to the next, but if the inner engineering isn’t there, our attention wanders. This is all the more important when someone writes, as McPhee usually does, of relatively unknown people, in whom we have no interest to begin with. For the writer, this sets the bar higher.

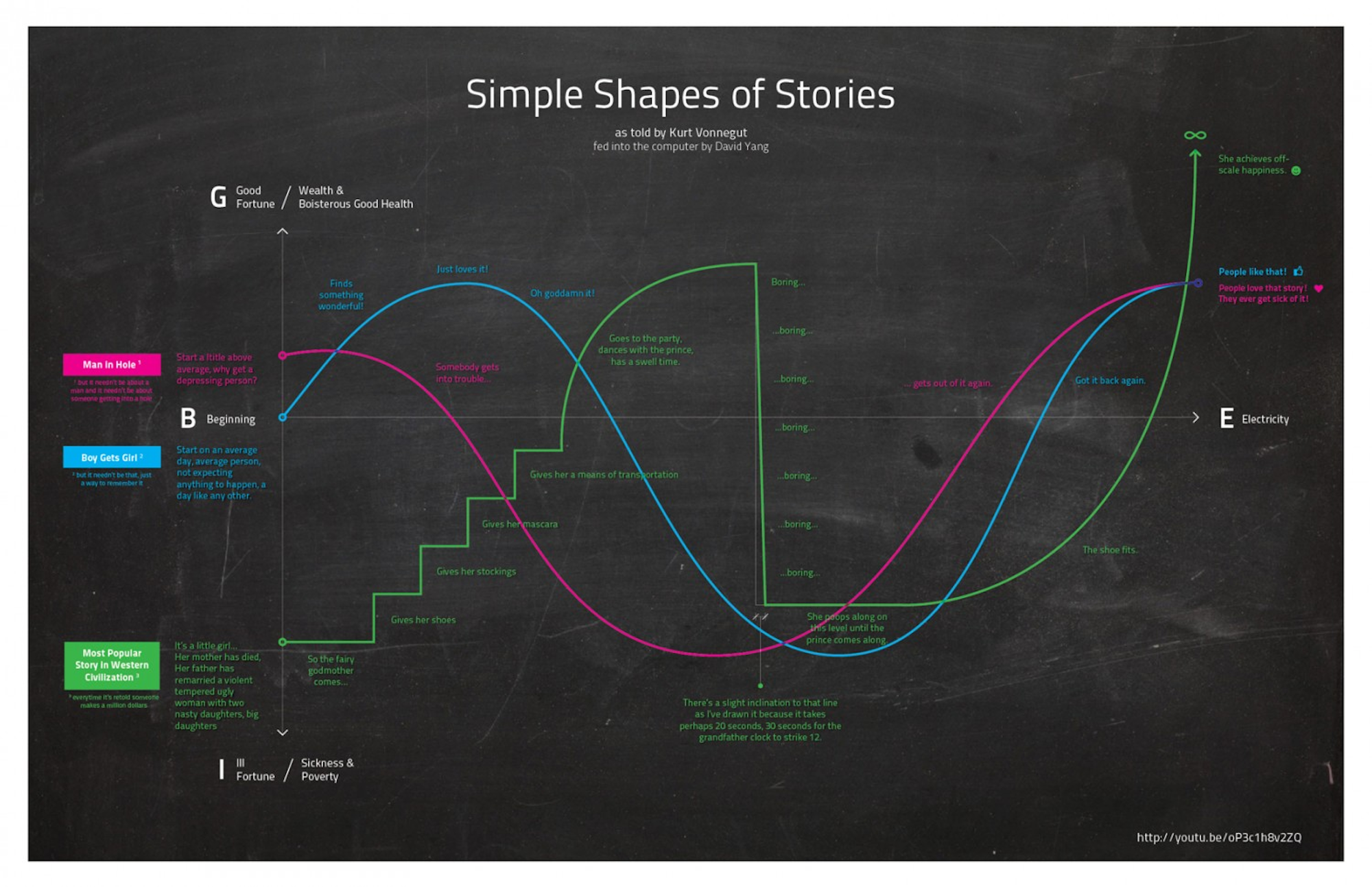

The question of structure is fundamental to narrative and yet it bedevils. Kurt Vonnegut once tried to make it simple. As a student, he dedicated his master’s thesis, at the University of Chicago, to the question of story shape. The thesis was rejected, but the theory has proliferated online — it survives in various forms as an instant tutorial on storytelling. Here is Vonnegut’s original presentation, via YouTube:

Graphic designer Maya Eilam re-rendered the lesson with an infographic:

He then moves on to Hamlet, delivering his signature blend of literary brilliance and existential philosophy:

The question is, does this system I’ve devised help us in the evaluation of literature? Perhaps a real masterpiece cannot be crucified on a cross of this design. How about Hamlet? It’s a pretty good piece of work I’d say. Is anybody going to argue that it isn’t? I don’t have to draw a new line, because Hamlet’s situation is the same as Cinderella’s, except that the sexes are reversed.

His father has just died. He’s despondent. And right away his mother went and married his uncle, who’s a bastard. So Hamlet is going along on the same level as Cinderella when his friend Horatio comes up to him and says, ‘Hamlet, listen, there’s this thing up in the parapet, I think maybe you’d better talk to it. It’s your dad.’ So Hamlet goes up and talks to this, you know, fairly substantial apparition there. And this thing says, ‘I’m your father, I was murdered, you gotta avenge me, it was your uncle did it, here’s how.’

CARO

Well, I learned that what I like to do is, I mean, the big difference between journalism and writing books for me is that in journalism you never had enough time to try to get it just right, and you always had questions that you didn’t have enough time to examine fully. It was a big deal if they gave you a month for an investigative series. At the end of the month you just had more questions. The more you learned, the more questions you had. So when I set out to do a book I said, “I’m not going to write this until I’ve found out everything that I can.”VONNEGUT

I was glad to come up through journalism rather than in the English Department, and I started out, and became, an anthropologist. You tell as much as you’re sure of at the very beginning. And so I always do. Students will write a story where three-quarters of the way through you realize this person was blind. The truth is actually that I do write leads and I try to have news hook and I guess maybe it’s a way to entertain.

And:

VONNEGUT

My daughter Lily complains because I talk too much, and that’s because I’m an actor and I’m trying out lines and it’s much better to say them out loud to hear what they sound like, but you have real people. Do you talk to yourself?CARO

I do, yes. I do, but I don’t do dialogue. I read my paragraphs out loud to hear myself the rhythm. To me rhythm is very important, and the only way I really hear the rhythm is by reading.VONNEGUT

I would do the same thing with commencement speeches, I want them to be shapely and to be fun possibly for an actor to say. Where’d you go to college?CARO

Princeton.VONNEGUT

I’ve heard of it.