Since the first stirrings of the Nieman Foundation’s narrative writing program nearly 20 years ago, the staff has tended a treasure trove of resource material devoted to excellence in journalistic storytelling. Much of that material went online first via the Nieman Narrative Digest and, in 2009, here at Nieman Storyboard. Storyboard 75 represents some of the most popular posts* from our archive so far. It also honors the Nieman Foundation’s 75th anniversary, which we celebrated cyberly last month with the Featured Fellow series, and last weekend IRL with a big bash at Harvard. You’ll find craft essays, interviews, how-to’s and a long list of highly recommended reading, along with analyses and author line-by-lines from our “Why’s this so good?” and Annotation Tuesday! series respectively. Enjoy!

(tips. so many tips.)

1) “The Moth’s Lea Thau on storytelling”

“The important thing in storytelling is to choose (a theme), so you have an organizing principle for your piece and you can give the audience a rope to hang onto.”

2) “News Feature v. Narrative: What’s the Difference?” by Rebecca Allen

“A narrative … lets the story unfold through character, scene and action — usually without summing up the story and telling readers what it’s about.”

3) Colin Harrison and Sam Gwynne on the editor-writer partnership and subject v. story

“One of the things we look for in editing writers is what kind of engine does he have? Is this a writer who works? Writers who work announce themselves without even trying. They turn stuff over quickly, they’re responsive and they get it done.”

4) “Interviewing for Story,” by Lisa Mullins, Public Radio International

“When I can get (story subjects) speaking in terms of chronology, in terms of a thought process, in terms of watching a story unfold and then maybe bringing it back to the beginning, that’s when the audience is naturally going to listen.”

5) Public radio’s Starlee Kine on story forms

“There are different kinds of stories. We have the-giant-thing-that-happened story. It’s so obvious and you can’t really mess up the interview because there are all these different parts. … And then there are other ones that are the personality-driven stories. And then there’s the ones that we called the sheer-force-of-will stories. You have a concept and it didn’t exist anywhere and you have to make it exist. It came out of your head and you have to force it into existence. Those are kind of my favorite stories, because it’s so satisfying to create something completely out of scratch…”

6) “14 Tips for Building Character,” by Rick Meyer

“Build characters by showing their actions. Sometimes you’ll be tempted to develop characters by saying who they are. Show them instead. Shaq was tall. That’s telling it. Shaq ducked to get through the door. That’s showing it.”

7) “Building Character: A Checklist,” by Jack Hart

“Characters who are remembered are those who are strong in some way — saints, sinners or a combination. For what will this character be remembered?”

8) “Building Character in Three Dimensions,” by Jack Hart

The typical 16-inch story doesn’t allow much space for character development, in any event, and a long digression to describe one of the sources would seem wildly out of place. But that doesn’t mean we can’t do a better job of bringing people to life in our stories, regardless of length or subject matter. Often just a passing reference will create an image in the reader’s mind, helping replace a distant quote factory with a real character.

9) “I wanted people who were beautifully imperfect,” by Isabel Wilkerson

“Perfection is not real, and readers cannot identify with people presented as perfect. … I wanted people who were willing to be who they really, truly were.”

10) “Keeping it real: how round characters grow from the seeds of detail,” by Roy Peter Clark

“To bring a person to literary life requires not a complete inventory of characteristics, but selected details arranged to let us see flesh, blood, and spirit. In the best of cases — when craft rises to art — the author conjures a character that seems fully present for the reader, a man standing against that very light post waving you over for a conversation.”

11) “6 Tips for Crafting Scenes,” by Laurie Hertzel

“You want the reader to feel like he’s right there with you. Scenes are all about action and movement and tension and detail. They should unfold moment by moment. It’s helpful to think in terms of making a movie or putting on a play: The curtain rises, the scene begins, your characters walk onto center stage and there’s action. They move through the scene, talking, fighting, eating, emoting, whatever. The curtain goes down, and the scene is over.”

12) “How’d you find that secret-compartments story, Brendan Koerner?”

“When I’m scouting for new stories to pursue, I do pay close attention to the press releases issued by the various United States Attorneys’ Offices — particularly the offices located in parts of the country that receive too little attention from New York-based reporters such as myself. Sifting through those releases once helped me find a tale I wrote back in 2011, about a Cuban-Latvian slot-machine hacker who ran afoul of the law. And so in January 2012, I went hunting for another true-crime yarn amidst the flotsam and jetsam of the U.S. Attorneys’ press-release archives.”

13) Collected wisdom: Orlean, Atkinson, Powers, Corchado, Britt, Merida, Bennett and more

“(The) model of going into a story as a student frees you out of that notion that you need to go in as an expert.” — Susan Orlean

14) “Everything you need to know about storytelling, in 5 minutes,” by Tommy Tomlinson

“What the story’s about is literally what happens in the narrative — who this character is, what goal he or she is trying to reach, what obstacle is in the way. The unique set of facts. What the story’s REALLY about is a way of saying, what’s the point? What’s the universal meaning that someone should draw from this story? What’s the lesson?”

15) “7 Writing Tips,” by Nora Ephron

“As a young journalist I thought that stories were simply what happened. As a screenwriter I realized that we create stories by imposing narrative on the events that happen around us.”

16) “How to look at your own stories more objectively,” by Amy Ellis Nutt

“Tighten sentences and sharpen details. If a word is vague, be more specific; if a phrase is overused, find another.”

17) “When journalists become authors: a few cautionary tips,” by Peter Ginna

“Just as it’s important to balance exposition and narrative, it’s essential in book-length nonfiction to deliver specific details while keeping the big picture clear in the reader’s mind — (a) balancing act that becomes more demanding at book length.”

18) “When I write the book: Nieman Reports on journalists who wrestle with long long-form”

“It’s a Long Article. It’s a Short Book. No, It’s a Byliner E-Book” is Byliner founder and CEO John Tayman’s look at a new publishing model, and a way to pull audiences toward an author’s entire body of work.

19) “CBC Dispatches: Sounding out your story,” by Alan Guettel

“Flesh out your characters. Ask subjects about the things that define them. Hopes. Fears. Food. Heroes. Music. Weapons. Family. Childhood. That’s how you find out that your Congolese driver hasn’t had three meals a day in 30 years. And the 11-year-old guerilla doesn’t like the AK because it pulls high and to the right. These things might work into a clip. More often they work into your narrative, alongside the other things we like. For example, physical descriptions: hands, faces, gestures, habits, tics.”

20) “Slow violence and environmental storytelling,” by Rob Nixon

“Tell stories no one else can tell. Writers, not least many environmental writers in the global South, have also sought to give narrative shape to the long emergencies that afflict their societies. Ken Saro-Wiwa, the Ogoni writer executed in Nigeria for his environmental activism, became a nimble, rhetorically versatile proponent of the rights of the minority peoples who inhabit the Niger delta. The delta provides 11 percent of America’s oil needs, but most Americans would be hard-pressed to put it on the map. Yet we are party to an ongoing ecological calamity: For over half a century the Niger delta has suffered the equivalent of an Exxon-Valdez sized spill every year. Saro-Wiwa — in his essays, memoirs, documentaries, and journalism — took it upon himself to become the teller of stories that before him scarcely ever reached the outside world.”

21) The power of place: Robert Caro on setting

“The greatest of books are books with places you can see in your mind’s eye: the deck of the Pequod while the barefoot sailors are hauling the parts of the whale aboard to melt them down for oil. The battlefield at Borodino as Napoleon, looking down from a hill on his mighty imperial guard, has to decide whether to wave them forward into battle. Miss Havisham’s room, the room in which she was to have been married, the room in which she received the letter that told her that the man she loved wasn’t coming, the room with the clock stopped forever at the minute she got the news, the room with the wreckage of the wedding feast that has never been taken away.”

And if you want to watch Caro talk about craft, here he is, with the Washington Post’s Anne Hull, at last weekend’s Nieman Foundation 75th anniversary festivities:

22) “The power of the parts,” by Roy Peter Clark, on ideas, organization, and focus

“This is not a linear process. To describe it correctly, I would need some sort of spinning cycles or double helix. If I can’t select out of the material I have, I say, ‘Maybe I don’t have a focus.’ If I can’t find a focus, I say, ‘Maybe I haven’t gathered enough stuff.’ It’s constantly sort of cycling back.”

23) “10 tips for editors,” by Lane DeGregory

“Read my story out loud. It does not sound the same when I read it to myself. I read all my stories to my dog, but I don’t get much feedback that way. (My editor) has a beautiful voice, and I love hearing my words when he reads them, and I can hear things like cadence, or this sentence is too long, or he got tripped up on these clauses.”

24) “8 reasons to put noise in your narrative,” by PRI’s Clark Boyd

“At its best, audio narrative doesn’t just immerse you in a place and time, but does so using the voices that best know and understand that place and time. There’s a saying in my business (slightly outdated now in the digital world): ‘Let the tape tell the story.’ If you judiciously apply some of the ideas above, you’ll find that the mediating effect of the whiny ‘personality’ can be minimized, and you can allow the listener to get that much closer to the story. My advice to all young radio reporters: Stay the hell out of the way as much as possible.”

(narrative, evolving: story forms)

25) “Story, interrupted: Why we need new approaches to digital narrative,” by Pedro Monteiro

“The main narrative of a story can be imagined as a string of scenes or episodes, like a TV series, where every added item is placed either at the beginning or the end of each episode. Every episode is structured so that it can be interrupted without breaking the narrative thread.”

26) Inside 40 Towns: Literary journalism at Dartmouth, with Jeff Sharlet

“I’ve always said (to students), ‘Look, you need to understand your writing practice as many things. And among others it is an economic practice. You are engaged in keeping yourself alive — emotionally, psychologically but also physically. You need to think about that. You need to think about what’s going to enable you to keep doing the work. You need to make those choices. You write a book so that you can write another book. You write a magazine story so that you can write another one, so that you can live this life.'”

27) “The importance of words in multimedia storytelling,” by Jacqueline Marino

“In his landmark book, Digital Storytelling, (Joe) Lambert discusses a process called ‘closure,’ in which the viewer recognizes the pattern of information relayed by the producer in ‘bits and pieces’ — images, video, graphics, text — and then completes that pattern in his or her own mind. In spoken word or a written narrative, we are operating at a high level of closure as we are filling in all the pictures suggested by a text or words from images and memories in our brains. … Storytelling with images means consciously economizing language in relationship to the narrative that is provided by the juxtaposition of images. There are two tracks of meaning, the visual and the auditory, and we need to think about the degree of closure each provides in relation to the other.”

28) Facebook as narrative: The Washington Post tries it out online and in print

“(This narrative) is fundamentally different, because the narration is provided by the original source. We had a little bit of a struggle early on in the project about just how much of our voice would be in the story. I was pushing all the way through for us to be very much on the sidelines and providing just the necessary bits of context, so that people understood who these characters were.”

29) Whitey Bulger: The Twitter trial narrative, by the Boston Globe’s Kevin Cullen

“I walked in and shot him,” Johnny says. “We had to get someone to bury him.” Joe Mac and Jimmy Sims were the men for the job.

30) Tori Marlan and Josh Neufeld on the webcomics narrative “Stowaway,” in The Atavist

“In comics, the reader has to make (narrative) connections based on visual cues, so everything in the script has to be visual and translatable by an artist.”

31) “Detroit: A love story:” Chuck Salter, Fast Company, and a live-storytelling approach

“Figuring out a new storytelling format is like writing a story. You have to start experimenting in order to figure out what works, what doesn’t and what you don’t know.”

32) Nonny de la Peña on the future of interactive storytelling, by Ernesto Priego

“I consider immersive journalism still under development, but Stroome is about trying to give users a way to start telling stories today, collaboratively, journalistically and from different perspectives. For example, rather than write a letter to an editor or call up a TV station to dispute veracity, the audience member could just remix the story, telling it the way they see it.”

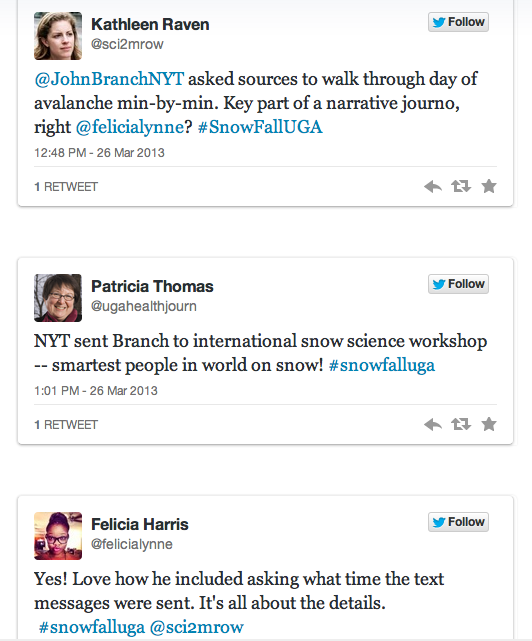

33) Inside the groundbreaking New York Times’ multimedia narrative “Snow Fall,” which drew on “Punched Out: The life and death of a hockey enforcer”

34) Evan Ratliff on The Atavist

“Our stories are more in the vein of long magazine pieces that are narrative in nature, that are character-driven. Some of them might just be a heist story – a kind of sexy magazine story. The other piece we’ve done is a story that you probably wouldn’t find in any magazine, because it’s not a story that anyone would publish. It’s a wonderful tale of a guy whose story has been lost but who was once well-known throughout the world. We really like lost stories like that, about people whose stories have vanished but they’re really quite remarkable. We have a couple of those that we’re working on. The main driver for us is not necessarily public-interest journalism or other types of journalism. It’s driven by the narrative. Party because we’re charging people by the story, we want people to feel like they are reading it like fiction and getting lost in it, missing their subway stops – things like that.”

35) Oliver Broudy on modern saints, magazines and crossing the border to Kindle Singles

“One of the reasons that I’m excited about long-form journalism and about the Kindle Singles thing is that I think for too long we’ve had these two paradigms for applying thoughtfulness to the world. One is the magazine-length feature, and one is the book. Whatever it is we want to address, we generally have to try to fit into one of those formats. There’s a lot of tension and strain that results because of it. The things that are too heavy end up getting underserved by the magazine piece, and things that aren’t quite heavy enough get wordy, redundant treatments in books that turn boring after 100 pages. In a way, the existence of these two paradigms of applying thoughtfulness to content has limited our ability to be thoughtful about the world we live in.”

36) Tanja Aitamurto on crowdfunding and the future of narrative journalism

“When the reader decides to donate, is there any better reward for a journalist than that — to actually have your readers pay to support you? Your actual readers pay you for the story. You might even see that relationship become more of a fan relationship. Also then the journalist can be seen as a sensemaker, an expert that the reader has hired. In the Dolly Freed case, the reader says, ‘Okay, this writer is an expert. I’ll support her.’”

37) How Twitter’s @longreads helps readers cozy up to digital narrative

“If we want to talk about the business of journalism down the line, I think there’s a lot of opportunity in taking journalism into an iPhone for mobile reading experience versus trying to do it on a laptop.”

38) “The future of print narrative,” by Tom Hallman Jr., The Oregonian

“At every newspaper, storytelling can be the tonic to help us get through (hard) times. For the writers, it means they connect with the readers. For the newspapers, it helps brand a paper in the community. People say, ‘I started to read it, and I knew it was your story.’ It helps if newspapers can say, ‘Once a week or once a month, we’re going to have a real story.’”

(essays on craft)

39) “Natural Narratives,” by Michael Pollan

“Whether we’re writing about nature or anything else, we can expand our concept of what narrative is. The more traditional definition is that narrative is made up of characters and their actions, set in scenes. This is true, but I’d argue that the characters don’t have to be human. You can build narrative out of systems: You can tell the story of how water gets from one place to another. You can build narratives out of other species. I’ve certainly done that; I’ve told stories about plants or animals and their history and used their point of view to animate a story.”

40) “The Four Noble Truths of Religion Writing,” by Peter Manseau

“When writing about religion, it is not the suspension of disbelief we should strive for, but rather the elevation of empathy over agreement.”

41) “Stories Are Everywhere,” by Adrian Nicole LeBlanc

“I keep story files. I clip and file whatever strikes me: new slang words, fashions, particular towns and neighborhoods, someone’s turn of phrase. My idea files are full of things that interest me, in ways that often aren’t clear to me. Some story ideas hit me immediately when I meet a person who engages my interest. Other ideas take years to develop in my mind, and even longer to sell to an editor. My story files provide the ammunition to convince an editor, to explain why a story is worthwhile. They allow me to draw from a whole pack of information, not just one or two anecdotes.”

42) “Voice and Meaning,” by Mark Kramer

“Brain scientists tell us that narrative is part of the scouting-for-trouble toolkit that has evolved right along with the human condition, an ancient cognitive skill that does for each of us what sentinels used to do for the towns they watched over from atop high encircling walls. Sentinel work is awfully close to what journalists do, in the daily paper or on the morning news. Reporters scan the modern world and report to local listeners and readers. They scout for trouble, and also for that antidote to communal trouble – sources of social cohesion within a community. They report on terrorists probing our gates, and they congratulate the local ball team, covering in one short newscast, community danger from without, and community bonding from within.”

43) “Endings,” by Bruce DeSilva

“Most newspaper stories just dribble pitifully to an end. Often they really don’t have endings at all. And newspaper people seem to be the only ones who have this fundamental problem with understanding that endings are important and figuring out how to make them work. Or if they get it, they don’t seem to practice it. And the reason for this is pretty obvious: the inverted pyramid.”

44) “The Persuasive Narrator,” by Roy Peter Clark

“The narrator can play a number of roles in the story. One strategy is simply to provide a slice of life, to tell a story that has no obvious moral.”

45) “Memoir’s truthy obligations: A handy how-to guide,” by Ben Yagoda and Dan DeLorenzo

“Inaccuracy is a problem in a memoir based on the extent to which it gets details as well as larger truths demonstrably wrong, depicts identifiable people in a negative light, fails to recognize the limits of memory, is poorly written, is self-serving, or otherwise wears its agenda on its sleeve. The more of these things it does and the more egregiously it does them, the bigger the problem is.”

46) “Seeking the Extraordinary in the Ordinary,” by Walt Harrington

“The artfulness required to do intimate journalism is not mostly a God-given skill, but craft. It’s crucial to think that way. Otherwise, we make the mistake of assuming that some people just have the knack. Some people do have the knack, but much of artful journalism, whether or not it is for ordinary people, is simply hard work — craft. I know, because whatever artfulness exists in my journalism was acquired, not inherited.”

47) “Breakable Rules for Literary Journalists,” by Mark Kramer

“The point of literary journalists’ long immersions is to comprehend subjects at a level Henry James termed “felt life” – the frank, unidealized level that includes individual difference, frailty, tenderness, nastiness, vanity, generosity, pomposity, humility, all in proper proportion. It shoulders right on past official or bureaucratic explanations for things. It leaves quirks and self-deceptions, hypocrisies and graces intact and exposed; in fact, it uses them to deepen understanding. This is the level at which we think about our own everyday lives, when we’re not fooling ourselves. It’s surely a hard level to achieve with other people. It takes trust, tact, firmness, and endurance on the parts of both writer and subject. It most often also takes weeks or months, including time spent reading up on related economics, psychology, politics, history, and science. Literary journalists take elaborate notes retaining wording of quotes, sequence of events, details that show personality, atmosphere, and sensory and emotional content. We have more time than daily journalists are granted, time to second-guess and rethink first reactions. Even so, making sense of what’s happening – writing with humanity, poise, and relevance – is a beguiling, approachable, unreachable goal.”

48) “The essence of story, in a 358-word song,” by Tommy Tomlinson

“Most of the details unfold in a conversation around the dinner table. Mama talks, then Papa, then Mama again, then Brother, then Mama one last time. When you get people talking together, reacting to one another, coming from different angles, that’s closer to real life than you, the interviewer, asking questions.”

49) “Viewfinder: Video journalism that works,” by Sean Patrick Farrell

“If you’re really going to have video be a part of the story, reporters need to know (that) from the beginning, for the best possible outcome. This entails thinking about everything from the pitch to the questions you ask a source before you leave the office – quite different than if you’re headed out with just a pen and pad. He says: I find myself now asking TV producer questions like, What does it look like when you do your job? If I followed you around all day, what would I see?”

50) “Meanwhile, back at the ranch,” a four-part series on storytelling, by Adam Hochschild

“People seem to assume that if they find something readable or lively, it’s likely to be a piece of fiction. Similarly, I think there is sometimes an assumption among scholars that your work will not be taken seriously if it sounds too accessible. … Historians from an earlier time, like Francis Parkman or Henry Adams, expected their work to be read by the general public. When Thomas Babington Macaulay wrote his “History of England,” he said he would only be satisfied if it displaced the latest novel from women’s bedside tables.”

51) “The Line between Fact and Fiction,” by Roy Peter Clark

“(John) Hersey made an unambiguous case for drawing a bold line between fiction and nonfiction, that the legend on the journalist’s license should read, ‘None of this was made up.’ The author of Hiroshima, Hersey used a composite character in at least one early work, but by 1980 he expressed polite indignation that his work had become a model for the so-called New journalists. His essay in the Yale Review questioned the writing strategies of Truman Capote, Norman Mailer and Tom Wolfe. Hersey draws an important distinction, a crucial one for our purposes. He admits that subjectivity and selectivity are necessary and inevitable in journalism. If you gather 10 facts but wind up using nine, subjectivity sets in. This process of subtraction can lead to distortion. Context can drop out, or history, or nuance, or qualification or alternative perspectives. While subtraction may distort the reality the journalist is trying to represent, the result is still nonfiction, is still journalism. The addition of invented material, however, changes the nature of the beast. When we add a scene that did not occur or a quote that was never uttered, we cross the line into fiction. And we deceive the reader. This distinction leads us to two cornerstone principles: Do not add. Do not deceive.”

(nieman storytellers)

52) Looking for a ready-made list of great storytellers? The Nieman Foundation counts distinguished writers and other storytelling pros among its alumni. Our recent Featured Fellow series highlighted some of the best, including Susan Orlean, Robert Caro, Anne Hull, Gwen Thompkins, Buzz Bissinger and Gene Weingarten.

(shop talk: storytellers on story)

53) Chris Jones on reporting for detail, the case against outlining and the power of donuts

“Any interview I do for a narrative story, particularly with people who don’t speak to reporters normally, I usually have a preamble where I talk about the questions I’m going to ask. I tell them, A story like this relies on details, I’m going to ask you what might seem like some really strange questions. If you don’t remember, that’s okay, don’t force yourself to remember things… If you spend enough time with people they get comfortable.”

54) “Sebastian Junger and the perfect storm,” by Elon Green

“I really like beginning stories by imagining them as the beginning of a movie. In the opening scene of a movie about Gloucester, what would the tracking shot be? Where would it come to rest? I think visually when I write. The sculpture on that church is really arresting and I thought, “I think I would pan across Gloucester and stop on that image.” I should say, having a Gloucester schooner instead of the Baby Jesus in Mary’s arms is such a stunningly pagan move that, as an atheist and an anthropologist, I was just charmed by it. Also, it communicates how frightening this job must have been, that they visualized the help they needed in that way.”

55) Ta-Nehisi Coates on “Fear of a Black President”

MIT’s Tom Levenson talks with the Atlantic writer about his National Magazine Award-winning piece on how “America has proved to be much more ready to elect a black president than to be governed by one.” Here’s Coates: “Once I had some vague notion of where I was going, I sat down to write. And, you know, it’s funny – I was just talking about this for class. Here at MIT and at any college, I’m trying to get my students to understand that great writing, good writing definitely, often starts off as a D. It is very rare that you sit down and you write an A. You know, you begin a D and you have to accept that what you do at first is probably not going to be very good. And you just have to accept that. So I really tried to cut off my editing sense. I really tried to cut off my sort of disappointment in whatever I wrote and just get a draft done. Get a draft done. Above all, get a draft done. And that initial draft, it probably had like “TK’s” in it. And not just “TK’s” like this person’s name but like section “TK’s,” like, “you need to write a paragraph about this.” The hard thing about that is I find the structure and the literary devices often clarify a point, and by clarifying a point or by clarifying a section, maybe it doesn’t belong where you think it did.”

56) “Leslie Jamison and the imprisoned ultradistance runner,” by Elon Green

“Part of what fascinates me about the essay form is that it seems to acknowledge — in its structural fluidity, its capacity — that phenomena in the world are ruthlessly — often surprisingly — connected; I wanted this essay to posit some of those connections between various societal structures of sentiment (the crutch and comfort of blaming, for example). I hate rhetorical hinges that pose clever but ultimately hollow connections between things — and am sure some readers feel I’ve done some of that in this piece — but I really did feel like the impulse to self-soothe by way of accusation — that feels like an important sentimental wire running between what happened to Charlie vis-à-vis the subprime crisis, and what happens with incarceration more generally.”

57) Amy Wallace and one of Hollywood’s ‘most despised and feared’ men, by Elon Green

“Many profiles — the best ones, I think — are a window into a world that the reader has never considered before. I make a point of looking for stories like that.”

58) “Pamela Colloff and the innocent man,” by Paige Williams

“I had upwards of 18 hours of interviews on tape and we were in almost daily communication as I reported and wrote the story. We usually communicated by email. In general, I prefer to not tape my interviews unless I’m speaking with the main character of the story or if I’m worried that a source may be litigious in the future. I find that I listen much better if I don’t record. But digital recorders are so easy that I’ve found myself recording more and more interviews (and taking worse notes).”

59) Eliza Griswold on religion, violence and reporting

“I had to write the book in layers. I started with the narratives and then, with my editor’s help, came to understand that the travelogue was not going to be enough, that there were much larger forces at play: geography and history and weather and centuries of human migration; and that the book, to be what it needed to be, was going to have to take all those factors into account as well. So it was really a process of layering, of going through and writing and rewriting. The narratives came first, and then came the issue of “what are the larger ideas here?” One of the things that I loved about doing the reporting this way was that I didn’t start with any conclusions. I didn’t start with trying to prove, or even disprove, the clash of civilizations. That was a great luxury. I could just travel along this line and see what was actually happening on the ground.”

60) Junot Díaz on imagination, language and Star Wars as a narrative teaching tool

“I’m no good at journalism, guys. Everybody else does that stuff way better than I do. There are so many of you who do this work in enormously important ways and approach it across a number of unique mediums, but I enjoy very much the fact that the lies that I write about the Dominican Republic in some way produce truth effect, produce knowledge. That they produce awareness. They produce news of the world.”

61) “Gay Talese has a Coke:” Gay Talese in conversation with Chris Jones

“Every night I type up – in the case of Frank Sinatra, for example, I had 33 days on that story, 33 dates. And each day might have two or three typed pages representing the total experiences of that day for me: what I remember, what I felt, what Sinatra was doing, what he wasn’t doing. I was describing as an observer on the scene, somewhat distant but still on the scene. After I’ve amassed all this material I go over it day by day by day and I summarize everything. So I have 33 summaries of 33 sets of notes from 33 days of being on the road. With those summaries I’m also reviewing once more, and once more, and once more what I’ve seen and what I’ve heard. And out of this becomes a kind of connection between the whole 33-day experience, and I see scenes. We all see scenes. When you’re on the road there are things there that are really scenic, if you’re on the road, if you’re outdoors. Well, sometimes when you write them, when you begin to write them, those scenes take on a sharpness, a focus, a particular specificity.”

62) Michael Paterniti on voice, rewrite, Bill Clinton, old cheese, and flying Spaniards

“A lot of things become very symbolic for me in the writing, so if the details are rich enough to construct a universe then perhaps out of that world comes the symbol or metaphor that carries meaning, that carries something I’m trying to say.”

63) Jack Hart on Storycraft and narrative nonfiction as an American literary form

“Most journalists most of the time write reports, and that’s a perfectly valid function of journalism – probably its most important function in the long run. When they attempt to tell a story, sometimes those old habits die hard, and they have a difficult time getting down the ladder of abstraction and entering the world of scenic narrative, where you’re describing specific events and specific scenic elements that unfold in, at least to the reader, what appears to be real time.”

64) Building better sentences: Constance Hale on verbs, scenes and rewiring bad lines

“If there’s a problem in the sentence, you fix it by going to the verb. Whenever I hit a muddy passage that’s how I straighten things out.”

65) Gene Weingarten on journalistic ethics: Two case studies from his career

“There’s a law that I just now named when I’m looking out at all of you. It’s the Law of Diminishing Investment. This is something that applies whenever you disclose something potentially bad to an editor. Here’s what happens: At every level that that decision is then kicked upstairs because nobody wants to take responsibility for it, the person making the decision is less invested in your story.”

66) Stephanie McCrummen on bare-bones writing, ‘working backwards’ and editors’ good ideas

“A lot of times I just let a story stop, rather than really writing an ending or thinking about it the way you think of a beginning. It’s probably the fear of overwriting again, or not wanting to be definitive, in terms of meaning.”

67) Eli Saslow on writing news narratives and creating empathy

“Where any good editor is indispensible, at least for me – and (David) Finkel definitely is – is that he’s super in-touch throughout the process. So that most of the time I’m coming up with the ideas, but if he’s not outright rejecting five ideas, he’s helping me home in on those ideas before hand, so that I’m going to the right place for the right reasons. Then when I’m there, he wants me to check in and talk about what I’m seeing, which is pretty much the same thing as reading out loud. Talking about it out loud helps me to begin to structure a story in my head and helps me figure out where to focus my reporting. He’s super-talented, even from afar, at having good ideas about what things to look for and watch out for.”

68) David Barstow on being fair, bearing witness and ‘doing something bigger with the story’

“One of the most important challenges for us (with ‘Deepwater Horizon’s Final Hours’) was, through the reporting and interviews we did with more than 20 of these crew members and a really careful sifting through of all the public testimony, putting together an incredibly extensive narrative that zeroed in on this very compressed period of time.”

69) Roy Wenzl on abuse narratives and victims’ voices

“The other thing I knew from having done narrative for a few years, and from having done child abuse stories in the past as a reporter and an editor, the way that the media often does these stories is that they write about them in the abstract – your typical weekender, with an anecdotal lede followed by summary news nut graf, followed by fact, followed by fact. And they’re facts that are just facts. When you write about things in the abstract, it’s very difficult for readers to get engaged with it. “OK, there’s this massive problem, and there’s very little I as a reader or as a citizen can do with it, so I’m just not going to engage.” But when you turn it completely on its head, the real theme of this story, the real unstated but obvious theme, is that this is how this stuff actually plays out in secret. When you’re hinting to the reader that this is how all these cases go — yet you wrap it around these central characters of the two girls and a hero once in a while, either the rescue woman or the detectives — it’s almost irresistible. People are just pulled along. They want to know what happened next to the girls. Which meant that I had to write it from the inside, so the reader was right there. I had to reconstruct scenes.”

70) Documentary photographer Lori Waselchuk and the ethics of narrative activism

“Look outside the traditional field of journalism for inspirations on how to get your work out. Right now I’d say the Internet can be considered traditional. To me in journalism, your feet have to be on the ground. You have to be interacting with people. You can’t report without coming face to face with people and feeling as well as hearing as well as seeing. How can you honestly translate that in different ways?”

71) L.A. Times reporter Christopher Goffard on structure, sympathy and story engine

“You’re striving to convey a sense of the inner life of the characters, the kind of thing novelists do and the great nonfiction writers like Gary Smith do. When you’re writing about drug addicts with mental illness, some of whom are career criminals and hustlers, some of whom may be giving you false or delusional or self-serving accounts of their lives, you have to be very careful. There are barriers, and you don’t want to counterfeit an intimacy you can’t legitimately claim. So the narrative’s very sparing in getting inside their heads. As a narrative writer, you’re losing a crucial weapon, and you have to find other methods.”

72) Vanity Fair’s Bryan Burrough on writing narrative and holding readers’ attention

“I think — in fact, I know — that I’m a lot pickier than some of my peers. I find a problem that too many people who attempt narrative journalism do is to think that applying the narrative form to material that’s subpar, that somehow elevates it. Well, it doesn’t. You’ve got to have the goods. I’m renowned, in fact, notorious probably, at Vanity Fair for throwing stories out after a month: ‘Sorry, not going to do that one.’ ‘Why? Why? Why? It was a perfectly good story.’ ‘No, it wasn’t good enough.’”

73) Gary Smith on intimacy and connecting with subjects

“To become a longform writer and to kind of immerse yourself in different worlds, it’s almost like a double-railed track. Not only do you grow as a writer, but that other rail of the track is huge. Part of it is something you’re developing – some sense of self, getting a little more at ease in your own flesh and bones. So much of what happens in the interactions between you as the writer and the subject hinges on their trust in you, their confidence in you. And so much of that hinges on how comfortable you are. Any uneasiness you bring is going to cost you dearly.”

74) Kiera Feldman on investigative narrative and trauma reporting

74) Kiera Feldman on investigative narrative and trauma reporting

“My early drafts were a mess. I left whole sections just sketched out as outlines, because there was so much material to try to pull together. I was totally overwhelmed. And I was continuously doing more reporting, right on up to closing time. Michael Mason, my editor, gave really great structural comments. He didn’t do as much line editing as I was used to in other stories. That was new for me; I’m used to having every sentence I write go through the wringer and come out different on the other side. He very rightly pointed out that the piece needed a richer sense of character. I’d been so focused on just pulling together facts that this whole cast of characters just got jumbled together. He made what proved to be a crucial suggestion, which was to think about Grace Church’s building as a character in the story, to show how it changed over time. Originally, the ‘gilded carousel’ final line came at the end of a kind of long 1,200-word lede, but then I moved it to the end of the piece. And the whole time that I was revising (while doing more reporting), I was working toward that gilded carousel. At the same time, I figured out that I needed to start the piece mid-scene with the “do not fondle” agreement. So that was a fantastic place to be: I knew where it began, and I knew where it needed to end up, and everything else would get figured out.”

75) Mark Bowden on the value of “beginner’s mind”

“Conventional journalism, conventional reporting, requires value judgments. You have to decide, really before you sit down to write your story, what’s the essence of this story? What’s the most important fact that I have to offer? What’s the second most important thing? There was a real rigid format to writing these stories. Writing a narrative, on the other hand, simply telling a story, to me, I realized, was more true. It was not only more fun to read and more fun to write, it moved out of the abstract world of newspaper journalism and into the real world, where there was a setting, there were people, and there were characters and action and dialog, and the story unfolded in a very comprehensible way. It also is a way of storytelling that respects the reader, who we can assume is intelligent enough to make up his or her mind about the significance of what it is that you’re telling them. It also left room – a well-told, true story — for differing interpretations of the story that was being told, just like life.”

76) Rebecca Skloot on the importance of structure

“Structure is all about making the story more rich. What I thought all along was that if I couldn’t find a way to do a structure that jumped around in time like that and told all three narratives at the same time, I’d lose a lot of the story, because the story of the cells and what happened to Henrietta take on such a different weight if you learn about them at the same time that you’re learning about the science, the scientists and her family, what happened to them and where they are now. To me, it was that I would have lost those things if I couldn’t have done the more complicated structure. But there was never a point where I thought, I have to leave out this one really important part of the story because it doesn’t fit in this structure.”

77) Pat Walters on endings, Walt Harrington on integrity, Chris Jones on why stories matter: scenes from the 2012 Power of Storytelling conference in Bucharest (founded by current Nieman Fellow Cristian Lupsa)

Here’s Walters, of Radiolab, talking about a Burkhard Bilger story about catfish noodling: “I read a quote recently from an American novelist named Colson Whitehead who was talking about this mantra that happens especially in creative writing classes in America, maybe here too. Writers and teachers always talk about show, don’t tell. You want to show people in scenes when you’re writing narrative. But Whitehead pointed out that he likes stories that show and tell. Because sometimes showing can be a crutch. Because you can show a scene and maybe you haven’t figured out yet what it means to you. And so I think this is one of the great scenes that shows you – you can see it, the whole moment happens in the son’s face – but it’s telling you something.”

78) Sports Illustrated’s Alexander Wolff on hooking the reader

“From an execution point of view, with historical pieces, the narrative is so naturally there that you don’t have to contort yourself to come up with a spine to the story. If you can somehow put enough enticing stuff up top before you rewind and get into the narrative in a more chronological way, you’ve got a really good chance to grab and carry the reader at least through the first third of it.”

79) National Book Award winner T.J. Stiles on telling good stories and asking big questions

“I believe that there is no reason why we have to sacrifice scholarly standards and investigation for reading pleasure. If we think of the great works of literature, whether they’re fiction or nonfiction, they’re a real treat to read. What I like to do in my writing is to tell good stories and ask big questions. I like to write about the making of the modern world. I want to write books that are about complex characters that tell compelling stories, and I want to give the reader a reason to turn every page.”

80) Charles Pierce on story goals

“I want the ideas to flow from one to the other. I want them to be surprising if they can be. I want the reader to go along in the same kind of evolutionary way, to have the themes strike them at the same point in the story that they strike me. But I don’t write with the reader in my head.”

81) Wright Thompson on identity, clarity, work habits and the deadline virtues of Lionel Ritchie

“I want to be in the chair writing by 6:30 (a.m.), and I want to be done writing for the day by 2. There are always five or six stories going at once so I need to sort of do the daily maintenance on them. I’m just much better right in the morning. And also, I can have a day ruined very easily, which I’m trying to get better about because it’s stupid to be superstitious, but, like, if I oversleep the day is shot for me. I can’t go start at 10. It’s ruined.”

82) “You will always have work, and it will be the best kind of work:” Richard Rhodes

“If you learn to write, learn to write well, learn to make people and events come alive in words whether fictionally or veritably. You will always have work, and it will be the best kind of work, work that uses, work that demands everything you’ve got. Who could ask for more? “

83) Andrew Corsello on empathy, the writer-editor relationship and breaking rules

“(‘The Wronged Man’) is one of only two perfect pieces I’ve written, because I was able to keep the piece in its own narrative bubble from beginning to end. (The other is “My Body Stopped Talking to Me” and is not online, having been published in GQ in 1995.) People talk about the bird’s-eye school of journalism, more or less The New Yorker, which is professorial and cool in tone, and distant, and the object is above all to explain in the most limpid terms possible what you need to know about a given story. I’m temperamentally different than that. Empathy is the be-all, end-all of my stories, both in terms of what I pick to write about and how I write about them. I want to find very emotional stories and come as close as I can come to recreate the emotional experience for a reader, and that means you want to do it novelistically.”

(recommended reading, listening, watching, etc.)

84) “Never Let Go,” by Kelley Benham French, Tampa Bay Times, about the author’s prematurely born child

85) “Beyond the Finish Line,” by Tim Rohan, New York Times, about a Boston Marathon bombing survivor

86) “Life of a Salesman,” by Eli Saslow, Washington Post, about a man desperate to sell swimming pools

87) “The Yankee Comandante,” by David Grann, The New Yorker, about an American ex-pat in Cuba

88) “The High Is Always the Pain…,” by Jay Caspian Kang, Morning News, on winning, losing, Vegas

89) “Fixing Mr. Fix-it,” by Diane Suchetka, Cleveland Plain Dealer, about a man whose arms were surgically reattached after an accident

90) “The Girl in the Window,” by Lane DeGregory, Tampa Bay Times, about a “feral” child

91) “The Peekaboo Paradox,” by Gene Weingarten, Washington Post, about a children’s performer

92) “Attacked by a Grizzly,” by Thomas Curwen, Los Angeles Times, about hikers and a bear

93) “Head Trip,” by Barry Bearak, New York Times, about a baseball player beaned by a ball

94) “The Meaning of Work,” by David Finkel, Washington Post, about unemployed black men

95) “The Ground We Lived On,” by Adrian Nicole LeBlanc, about the death of her father

96) “The Old White Oak,” by Elizabeth Leland, Charlotte Observer, about an embattled tree

97) Two boys and a basketball, by Anna Griffin, The Oregonian, about an act of sportsmanship

98) The woman who disappeared, by Michael Kruse, Tampa Bay Times, about an unthinkable death

99) “Fighting for Life 50 Floors Up…,” by Jim Dwyer, New York Times, about a 9/11 escape

100) “The Town That Lived in Silence,” by Barry Siegel, L.A. Times, about a child’s murder

101) “A Hanging,” by George Orwell, New Adelphi (1931), about an execution in colonial-era Burma

102) “Final Salute,” by Jim Sheeler, Rocky Mountain News, about a military bearer of bad news

103) “An Imam in America,” by Andrea Elliott, New York Times, about a Muslim cleric in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn

104) “The Journey of Judge Joan Lefkow,” by Mary Schmich, Chicago Tribune, about the murder of a judge’s husband and mother

105) “Enrique’s Journey,” by Sonia Nazario, Los Angeles Times, about a young boy who came to the United States from Honduras

106) “A Wicked Wind,” by Julia Keller, Chicago Tribune, about a tornado

107) “Angels & Demons,” by Thomas French, St. Petersburg Times, about the murder of a mother and her two daughters

108) “A Gypsy for Our Time,” by Adam Hochschild, Mother Jones, about a man’s childhood with gypsies

109) “Digging JFK Grave Was His Honor,” by Jimmy Breslin, N.Y. Herald Tribune, about a gravedigger

110) “Una Vida Major,” by Anne Hull, St. Petersburg Times, about N.C. migrant workers

111) “Black Hawk Down,” by Mark Bowden, Philadelphia Inquirer, about a battle in Somalia

112) “Forest Haven Is Gone,” by Katherine Boo, Washington Post, about failing the mentally retarded

113) “The Boy Behind the Mask,” by Tom Hallman Jr., Oregonian, about a disfigured boy

114) “Mrs. Kelly’s Monster,” by Jon Franklin, Baltimore Sun, about a surgeon and a tumor

And here’s Franklin talking about the piece for our Annotation Tuesday! series: “It is no accident that the first verb in this story is an action verb. The use of present tense tends to make the story more immediate, but it increases the pressure on the writer, who must supply an endless stream of detail to make the immediate nature of the story seem real. Because of the increased technical problems with present tense, the technique must never be used lightly. Also, present tense is usually unsuitable for long pieces.”

115) “The French Fry Connection,” by Richard Read, Oregonian, about the economy

116) “Spectacle,” by Ben Montgomery, Tampa Bay Times, about a 1934 lynching in Florida

117) “After the Sky Fell,” by Brady Dennis, St. Pete Times, about a grieving toll booth worker

118) Joan Didion on dreamers gone astray, by Jennifer B. McDonald

Setting is foreshadowing, and this is a diabolical patch of ground: a site where serpents multiply, where sins will be committed, where, according to law enforcement officials, Lucille planned to “spread gasoline over her presumably drugged husband and, with a stick on the accelerator, gently ‘walk’ the Volkswagen over the embankment, where it would tumble four feet down the retaining wall into the lemon grove” – into the greenery of nightmare – “and almost certainly explode.” In Didion country, burning bushes become burning Volkswagens. People are delivered not into a land of milk and honey, but to the side of a dark and lonely road, where they’re roasted to a crisp.

119) David Foster Wallace’s “A Ticket to the Fair,” by Brent McDonald

Part of what I like so much about this piece is the simplicity of Wallace’s conceit. He goes, he sees, he feels, he ponders. And he writes 15,000 gripping words in time-stamped, straight chronology. It’s ostensibly a light, playful assignment — commissioned, Wallace suspects, because “every so often editors at East Coast magazines slap their foreheads and remember 90 percent of the country lies between the coasts, and figure they’ll engage somebody to do pith-helmeted anthropology about something rural and heartlandish.” What Wallace delivers instead is a strangely funny journey into a monoculture heart of darkness, minus Mr. Kurtz.

120) Danny and the carjackers and the Boston Marathon bombing, by Roy Peter Clark

This story should remind us of how rarely dialogue appears in breaking news, with reporters depending more often on quotes gathered after the fact. Even though he is using a single source (the bombers being unavailable, one dead, one arrested), the writer chooses to re-create the dialogue in the car based on Danny’s recollection. I count at least 12 paragraphs containing dialogue such as: “Don’t look at me!” Tamerlan shouted at one point. “Do you remember my face?” / “No, no, I don’t remember anything,” [Danny] said.

121) E.B. White and the sick pig, by Betsy O’Donovan

The narrative essay isn’t a self-help manual; if we do get any help, it’s to see that we are not alone. The first-person narrative is an invitation to consider the human condition, and part of that condition is indignity.

122) John Jeremiah Sullivan and “Upon This Rock,” by Paul Kix

It is not only Sullivan’s signature piece but also a great example of a writer having patience, revealing what he truly wants to say only at the appropriate moment, which in this case comes about halfway through the piece. Sullivan is much too smart to work within the shadows of an inverted pyramid, and the story is better – memorable; re-readable – because of it.

123) Dan P. Lee and Travis the killer chimp, by Peter Trachtenberg

The overwhelming temptation for most writers would be to begin with that scene of carnage, going either for grotesquery, the maimed woman lying in the driveway in a pool of her own blood, or pathos, the dead chimp clutching his bedpost at the end of a trail of his. But for Dan P. Lee of New York magazine, “Travis the Menace” (the jokey title is the only thing about it that feels wrong) is a story of omissions. Its power derives from what Lee doesn’t say or postpones saying until absolutely necessary. Of course, the delayed payoff is one of the hallmarks of suspense, but here Lee’s reticence seems to reflect deeper questions of how one tells certain kinds of story, whether it’s even possible to tell them.

124) Buzz Bissinger and the fabulist, by Deborah Blum

“Shattered Glass,” the 1998 story he wrote for Vanity Fair, also displays Bissinger at his best, a perfect balance of dogged research, astonishingly well-realized characters, told with a thinker’s narrative voice, one that muses, and ponders, and shares in the struggle to understand how a young writer could go so wrong. That’s undoubtedly one reason the piece fostered an art-house film of the same name.

125) David Grann and Sherlock Holmes, by Justin Ellis

A chateau! A curse! Deception and a Russian princess! And Grann’s just getting started. He’s clearly in the process of spooling up the thread to lay out the stakes of the story. Once the prized documents take a turn for Christie’s auction house the Sherlockian scholar grows more desperate and paranoid. The paragraphs race forward, the pace quickens, each sentence becomes so compressed and descriptive you feel like you can’t breathe. (In a good way, of course.) You’re worried about Green and what will happen to Conan Doyle’s archive. And then, just after you’ve gotten 1,000 words deep into the mystery, the body shows up.

126) John McPhee and the archdruid, by Adam Hochschild

A key secret of McPhee’s ability to make us care about his vast and improbable range of subject matter lies in his engineering. From the pilings beneath the foundations to the beams that support the rooftop observation deck, he is the master builder of literary skyscrapers. Other writers may have more glittering prose (although his often glows bright) or weave more elegant metaphors, but no one has built such an interesting and varied array of structures. With many authors of narrative nonfiction, even well-known ones, I often feel that structure is almost an afterthought: An array of lively scenes is arranged more or less chronologically, with one that feels like a good place to start placed at the beginning and one that seems to wrap things up placed at the end. But when McPhee picks up his pen, I sense a writer thinking long and shrewdly about structure before he even puts a word on paper.

127) Nora Ephron and the thing about breasts, by Wesley Morris

As a human being, her most powerful quality was that even though she was a very particular, very specific type of woman – liberal, Jewish, affluent, ceaselessly nostalgic, an Upper West Sider – what she observed about American life, her friends, frenemies, and herself was universal. As a writer, that universality was achieved through exaggeration, by performing modesty, by making whatever she could seem like the most, the least, the best, the worst, the first, the last, the only. She used hyperbole the way the painter Yves Klein used blue – it was her favorite color. She used it as shorthand for other, larger truths and characterizations.

128) John Jeremiah Sullivan and partisan politics, by Ann Friedman

Politics should, in theory, be the subject of some of the most compelling narrative journalism. There’s built-in drama! There are winners and losers! The stakes are high! That’s why it’s so depressing that most politics stories, even those of the narrative variety, are painfully boring. They tend to fall into one of two traps — and I don’t mean right or left. Sometimes they’re “objective” to a fault, stripped of all perspective and written as a description of an ideological Pingpong match in which the reporter, if she gets too close to the action, reduces herself to an awkward ghost. (“A visitor was offered a glass of water.”) Then there are pieces with the opposite problem: The writer, seemingly by design, uses every quote and detail to confirm her assumptions about the people on both ends of the American political spectrum, and does little more than recite familiar arguments and retrace caricatures that were first doodled decades ago.

129) Calvin Trillin and classic Edna Buchanan, by Ben Yagoda

“Covering the Cops,” like all of Trillin’s work, is journalism in the form of essay, or maybe it’s essay in the form of journalism. On the journalistic side, it is grounded in (very) deep reporting. On the other hand, it indulges in none of the egregious conventions of magazine profiles: present-tense scenes; gratuitous insertion of the author’s opinions and activities; catchphrases and clichés; and breathless, breezy, false or self-satisfied language.

130) Roy Blount Jr. lets Jerry Clower talk, by Steve Oney

The fact is that New Journalism at its best requires a depth of reporting that fewer and fewer contemporary practitioners are willing to pursue. “Knock ’im Out, Jay-ree!” does something I wish more profiles did – it surprises you. Although Clower grew up in a part of Mississippi where segregation was rampant, and while his humor appealed chiefly to white audiences, he was pro-civil rights. Blount hints at Clower’s progressivism near the top of the article, then elaborates at the conclusion. Clower’s children attended integrated public schools. In the late ’60s, Clower shopped at a store boycotted by racists – a gutsy decision at the time. Not that Clower mentioned any of this in his act. He didn’t want to convert audiences. He wanted laughs.

131) Didion, Hemingway and mathematically musical writing, by Adrienne LaFrance

The penchant for counting reveals what may seem like another paradox, but is actually the lifting of a veil: Didion shows that her language is musical but also mathematical, that she engineers her writing to sing.

132) Malcolm Gladwell on ketchup, by Tim Carmody

Malcolm Gladwell is known, for better or worse, for books, stories, and essays that identify something counterintuitive. At first you think it’s like this, but really it’s like that. But his best feature writing, again, is better than that. Even as illustrative chunks fall out of them, the essays as a whole don’t come with easy, business-retreat-ready takeaways. They’re neither intuitive nor counterintuitive, but engage in acts of intuition, a playful oscillation between irreconcilable poles. They clarify your perceptions by revealing the inadequacy of your concepts. They are intelligence-games.

133) Michael Paterniti’s painted ghosts, by Thomas Curwen

Paterniti’s style with its repetitive rhythms, its subordinate clauses and discursive participles might be considered indulgent. Perhaps it is. Perhaps too, in a day and age when the overwhelming pressure is to write with concise brevity, it is an artifact, a throwback to another time and place. … I hope not, for I always thrill to the opening of this story with its cadences of ocean brushing against a rocky shore – and to the subsequent recounting of the events on and after Sept. 2, 1998, when Swissair Flight 111 crashed into the Atlantic Ocean, five miles from the village of Peggy’s Cove, Nova Scotia.

134) Susan Orlean maps orchid obsession, by Andrea Pitzer

Orlean builds her study of obsession out of a vocabulary of desire and devastation, ranging from the apocalyptic to the sexually charged. Laroche’s own “passions boil up quickly and end abruptly, like tornadoes.” In the Fakahatchee, the rocks have crevices, the trees have crotches, and the orchids invite erotic speculation. Mere friction is enough to ignite the grass, literally setting cars on fire, leaving behind “pan-fried tourists” and the carcasses of burned-out Model Ts.

135) J.R. Moehringer KO’s a mystery, by Tommy Tomlinson

I’ve read this story at least 100 times since it appeared in the L.A. Times Magazine* in 1997, and my bones still ache with envy. Moehringer has command of all the storyteller’s tools here – rhythm, pacing, metaphor – and I’ve spent many an hour taking the story apart like an old radio. But what I love about this story the most is a simple thing that shows up in far too few nonfiction narratives: Mystery.

136) David Foster Wallace on the vagaries of cruising, by Megan Garber

But Wallace isn’t just a writer. He is a philosopher with a writer’s imagination. And “Shipping Out,” despite its lyricism (“I have felt the full, clothy weight of a subtropical sky”), is an argument whose poetry and provocations orbit around a single point: “There’s something about a mass-market Luxury Cruise that’s unbearably sad.” A thesis Wallace will prove through taxonomic considerations of ship-borne sorrows, through vignettes conveying both humanity and the absence of it, through rhythmic repetitions of the word “despair,” through inventories of assorted atrocities that have, in the topsy-turvy moral terrain of the Seven-Night Caribbean Cruise, adopted the guise of Mandatory Fun.

137) Sandra Cate on DIY cooking in a county jail, by Sarah Rich

There’s nothing terribly unique about allowing a subject to do some of the heavy lifting by running a quote, but the way the author chops up and reassembles the various descriptions of spread also functions as a verbal reflection of the thing itself. She maintains her role as a scholar, using the subjects’ voices and a few spare personal impressions to create a much stickier and more dynamic cultural illustration than your average anthropological report.

138) NPR’s Daniel Zwerdling on golden radio, Yoda and the Robert Krulwich moment, by Julia Barton

One thing that’s clear as Zwerdling talks about interviews: He listens on many levels. He’s fascinated by what people are telling him, and comfortable if they get emotional. But he’s also thinking about the needs the rest of us will have later – the way that we require concrete information, chronological accounts and vivid details to enter another person’s story. If Zwerdling has to ask basic, “obvious” questions over and over to break that story down on tape, then it’s fine with him.

139) Tom Junod on Mister Rogers, by Susannah Breslin

For me, the piece is a talisman. It’s a chant, or what you remind yourself of when everything goes wrong, or a mantra about compassion that does not easily translate into any Western language. The story works because it speaks to you as if you are the child you once were. It refuses to be snarky and dares to move you. Its author subjugates himself to his true master – the subject – in this case, the man we spent our collective childhood rapt before in the blue glow of a screen: “Mister Fucking Rogers.” Most stories move you forward. That’s how stories work: They unspool. Instead, Junod’s paean is a return, a transgressive retreat to a place where, before we fell from innocence, every day was a wonder and tying our shoes was a miracle.

140) Alma Guillermoprieto on Bogotá, by Jay Caspian Kang

A less gifted writer, even if she had chanced upon the genius of starting this piece with glaziers, would have taken a more somber tone. The question “How are these people living like this?” would have resonated throughout the piece. In Guillermoprieto’s hands, the glaziers retain their humanity, their humor and their ambition. They are not sacrificed to clumsy invective about foreign countries and George H.W. Bush and Pablo Escobar and who is at fault. It takes a hell of a reporter to write about violence with confidence and an appropriate level of humor. If nothing else, Guillermoprieto’s reports from Latin America in The New Yorker are a primer on how to shrug off the early, easy angles (those dripping with significance) and find the guts of a story.

141) Raymond Chandler sticks it to Hollywood, by Maud Newton

His complaints offer a fascinating snapshot of what it was like to write for pictures at the end of the Second World War. Yet his concerns about the way storytelling by committee tends to impede creativity and destroy narrative are timeless. “The volatile essences which make literature cannot survive the clichés of a long series of story conferences,” he writes.

142) W.C. Heinz on Air Lift, son of Bold Venture, by Chris Jones

Heinz never makes the mistake of telling us too much, of becoming sentimental or maudlin. We see the blood. We hear the jockey’s crying. We shiver with each clap of thunder and the coming rain. These are the only things that matter in the world.

143) McPhee takes on the Mississippi, by Carl Zimmer

McPhee builds articles like few other journalists can. He scrupulously avoids all stock tricks. His paragraphs encompass worlds. He writes from a dictionary full of strange words: revetments, whaleback, distributaries. They’re not obscure words McPhee chose to make the reader feel undereducated, but the precise language required to describe something most people know little about. It takes time to submerge into this language – this is not a story to shave away one iPhone screen at a time.

144) Truman Capote keeps time with Marlon Brando, by Alexis Madrigal

There are two Russian critical terms that are helpful here: fabula and syuzhet. The fabula is the real chronology of a narrative: Brando was born at such and such a time, grew up, and meets up with Capote in 1957. The syuzhet is how the story is told, its internal narrative time. How you convert fabula into syuzhet is storytelling, and Capote is dazzling. He weaves big time (a life) into little time (the hours), always working at two scales. For all its descriptive frippery and meandering actor monologues, the profile is set in reassuring 4/4 time. We never really leave that room in Kyoto even though Capote sweeps across Brando’s entire life.

145) “What’s on your syllabus?”

The reading lists — with liner notes — from narrative teachers including Madeleine Blais, Jeff Sharlet, Rebecca Skloot, Jacqui Banaszynski, Mark Bowden and more. Sharlet: “I assign (Joan Didion’s Slouching Towards Bethlehem) for the same reason most people assign it: because it’s one of the books that made me want to be a writer. That may have been generational, though. My students like it, but they don’t love it. None come to class wearing oversized sunglasses.”

146) “Professor Hersey: One student, the iconic author of Hiroshima, and six timeless takeaways,” by Peter Richmond

146) “Professor Hersey: One student, the iconic author of Hiroshima, and six timeless takeaways,” by Peter Richmond

“If what you leave out is essential, then the details you choose to leave in must be essential. (i.e.: The dank, decaying, ominous scent of a jungle is relevant if the man smelling it might be about to die from an unseen bullet, but maybe not if your story is of the prison road gang laying a highway through it).”

147) Chris Jones on the Zanesville zoo massacre

“What Jones doesn’t do is instructive. The words power and powerful do not appear in the piece; neither does the word fierce. Strong shows up only once, describing a muzzle blast. The term beautiful in reference to the animals clocks in once, and then only as part of a quote. Jones doesn’t waste words telling readers how to feel about what happens. Instead, he sticks with the momentum of events on the ground, delivering the unforgettable image of a tiger lit by headlights stripped down to its disrobed spine by a bullet.”

148) “Words about pictures: Errol Morris’ digital script”

“Best known for his films The Fog of War and The Thin Blue Line, Morris has more recently been building an eccentric, hybrid form of writing in his work for the New York Times’ Opinionator blog. His latest five-part series only dips a toe into the lyrical scene-setting or expository arc readers might expect from a standard essay. When he does adopt a traditional rule — “Use dialogue” — Morris bends it to his will, plugging in whole conversations, sometimes allowing the script of a phone call to run continuously for thousands of words, morphing his essay into an interview.”

149) Jeanne Marie Laskas on The People v. Football

“Laskas brings together two classic narrative strategies to impressive effect: She tackles big issues though attention to tiny details and tells her story largely through dialogue. The story opens and closes with extended conversations between McNeill and his wife, Tia, who left him in 2007 but still coordinates much of his care. In between, we get comments from an online message board, a discussion between commentators on Monday Night Football, and interactions between Fred and those who document his diminishing mental capacity.”

150) Rick Moody on an “amazing tale”

“The title evokes a tradition in which sideshow oddities and wonders are used to titillate readers and draw them in, a tradition not entirely unfamiliar to journalists. Novelist and blogger Moody slides elegantly into his story, using “us” in the first paragraph to join the crowd of readers watching what will happen as Kimberly Reed meets up with Paul McKerrow, her high school identity.”

*You may notice that this list runs longer than 75 entries. Think of it as a Greatest Hits album with bonus tracks. Happy reading.